Flowing from headwaters hundreds of miles north in the hills of New York and northern Pennsylvania, the Delaware River forms the backbone of the Delaware Valley. It acts as the area’s economic gateway to the wider world, allowing container ships to access Philadelphia and its surrounding area. It holds great recreational value for locals, providing an opportunity for fishing, boating, and tubing.

However, without a doubt the most important service the river provides is the drinking water it brings for the area’s population. With the drought in southern New Jersey in recent months, though, it appears that water supply may not be as reliable as some may think.

The Delaware River Basin Commission estimates that roughly 14.2 million people rely on the Delaware Basin for their water supply, a sum which includes nearly all of the Delaware Valley’s population. Many municipalities, such as the city of Philadelphia and adjacent towns in southern New Jersey, draw their drinking water directly from the river, supplying their residents with the Delaware’s bounty.

While this drinking water has still yet to be affected, the rising threat of saltwater intrusion poses a major danger to the area’s water supply.

“It’s [saltwater intrusion] happening in the background all the time,” said Charles Schutte, a biogeochemist and an assistant professor of environmental science at Rowan University. “In any estuary, any place where there’s a mixture of freshwater and seawater happening, there is a balance between seawater pushing in on high tides, and then that seawater flowing back out on lower tides and freshwater flowing in.”

While this is an entirely natural process, alarm bells are raised when seawater is able to advance further up the river than it normally would, and if the saltwater reaches far enough upriver, it may reach local water intake plants. If saltwater reaches where these plants take in their water from the river, they would run the risk of sending out impotable water (water unsuitable for drinking) to the people who rely on the Delaware River for their water supply.

With a river like the Delaware which is, directly or indirectly, fed by rainfall, drought means less freshwater flowing through the river, and when less freshwater is available to fill the river, saltwater from the Delaware Bay moves further upriver to take its place.

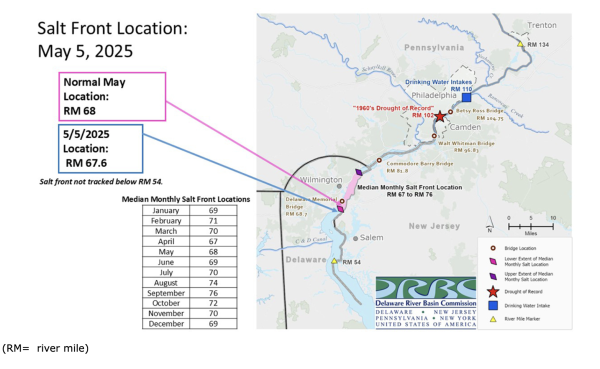

“There’s a threshold where, when it’s too salty, basically, and where that threshold is, is called a ‘salt front,’” said Schutte, “and so there’s monitoring that happens down the Delaware River… monitoring that takes place to figure out where the salt front is. It’s this thing that’s tracked carefully and recorded, if the salt front starts moving too far up, which is a natural thing that would happen during a drought, then there’s less freshwater flowing down the river.”

The recent long-term stretch of drought the area has faced in recent months is anything but normal conditions. Since the autumn of 2024, the entirety of the Delaware Valley has endured varying degrees of drought, forcing the entire region to grapple with an unusual lack of rainfall. Without that usual rain, the amount of water available in the region to find its way into the river, either through tributaries or direct runoff, directly decreased, causing a net loss of the volume of freshwater in the river as a direct result of the drought.

With the salt front moving further and further up the river, both those responsible for providing local communities with water and those responsible for managing the flow of the river as a whole have both moved to prepare for what further drought could bring.

“Whenever there’s a drought condition that’s something that’s closely monitored, that saltline,” said Brian Rademaekers, a spokesman for the Philadelphia Water Department. “Historically for our Baxter Plant on the Delaware River [one of the main water treatment plants supplying Philadelphia with its drinking water] it’s never been an issue, the closest was in the Sixties there was an extended drought, and at all times it was being monitored.”

As local water organizations like the Philadelphia Water Department and similar agencies and companies located across the river in South Jersey continue to keep an eye on the encroaching seawater, larger organizations are considering how the river must be managed not only at its end, but at its very beginning as well.

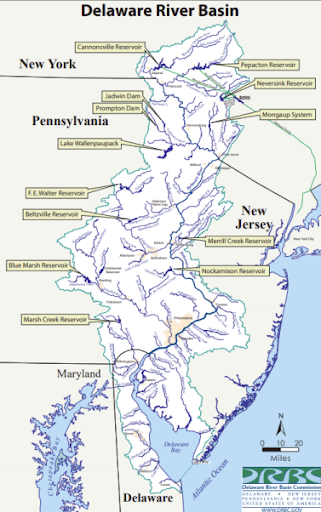

“Reservoir storage [mainly three reservoirs in upstate New York] have been a part of the ‘drought response.’ This involves water being released to help push the water further downstream to help protect the New Jersey and Philly drinking water intakes on the tidal Delaware River,” explained Julia Palmer, a member programs and development associate for the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, a non-profit organization devoted to river advocacy.

Indeed, reservoirs and reservoir management provide a unique opportunity for river management and maintenance. Overseen by the multi-state Delaware River Basin Commission, the adverse effects of both drought and flooding are able to be minimized by the strategic opening and closing of man-made reservoirs, tailoring the river’s flow to the current environmental conditions.

“The thing that’s interesting about the Delaware River is that the river discharge now is largely a human-controlled process … it’s a pretty carefully monitored and maintained system,” said Schutte, explaining the use of reservoirs in Delaware River management. “Even in a drought, we’re controlling the release of freshwater into the estuary to make sure this salt front doesn’t make it too far up the river.”

While the salt front has yet to come near the site it reached in the 1960’s “Drought of Record,” both due to lessening severity of the current drought and careful use of reservoir management, and with the high it reached in November 2024 not being exceeded since over the course of the current drought event, it is still far too early to stop worrying about the state of saltwater intrusion into the Delaware: the Delaware Valley is still in drought, putting the river and the reservoirs it draws from in continued jeopardy.

“We had reservoirs at pretty historic lows during the peak of the drought in the fall,” said Schutte. “This drought is ongoing, it’s not as severe as it was in the fall, but we still have a substantial rainfall deficit to make up.”