Lower Alloways Creek Township in Salem County is supporting the rise of a new American industry: offshore wind.

The state has started developing infrastructure to accommodate a new wind port in Lower Alloways Creek, which is located on the Delaware River. Kris Ohleth, Director of the Special Initiative on Offshore Wind at the University of Delaware, stressed the importance of the Salem County port’s invaluable location.

“Right there, in the Lower Alloways Creek, on the Delaware River in New Jersey, is really a perfect spot for sourcing service to so many of these offshore wind projects that are planned throughout the mid-Atlantic region,” she said. “It has an opportunity to not only serve as projects for offshore wind in New Jersey but also to our neighboring states like New York, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia.”

New Jersey’s official website stated: “The New Jersey Wind Port is the nation’s first purpose-built offshore wind marshaling port, promising to position New Jersey as a hub for the U.S. offshore wind industry.” Construction on the project began in Salem County in 2021 with completion expected in 2023, according to the state’s website.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy (BOEM) management describes offshore wind as “an abundant domestic energy resource that is located close to major coastal load centers. It provides an efficient alternative to long-distance transmission or development of electricity generation in land-constrained regions.

“Offshore wind facility design and engineering depends on site-specific conditions, particularly water depth, seabed geology, and wave loading,” according to the BOEM website. “As the wind blows, it flows over the airfoil-shaped blades of wind turbines, causing the turbine blades to spin. The blades are connected to a drive shaft that turns an electric generator to produce electricity.”

According to the federal Department of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, data on technical resource potential suggests offshore wind resources are abundant, stronger, and more consistent than land-based wind resources.

“While not all of this resource potential will realistically be developed, the magnitude—approximately 2 times the combined generating capacity of all U.S. electric power plants—represents a substantial opportunity to generate electricity near coastal, high-density population centers,” according to energy.gov.

The New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA) estimates to spend $300 to $400 million in public funds on the New Jersey Wind Port.

In addition to generating a substantial amount of clean energy, New Jersey expects the wind port to stimulate up to $500 million in new economic activity within the state and region each year.

According to the NJEDA, the wind port will produce 1,500 permanent jobs in manufacturing and operations, including assemblers, drafters, computer programmers, and technicians. Hundreds of construction jobs will spawn as well.

The construction of the port will be built using union labor under a project labor agreement. These jobs will accommodate a diverse, technical, and highly skilled trades workforce, the NJEDA wrote on its website.

“It’s a really great opportunity for the state of New Jersey to be involved in the economic development opportunity associated with the industry,” Ohleth emphasized.

The Special Initiative on Offshore Wind (SIOW) is an independent project and policy think tank that works with state and federal policymakers to advance the sustainable development of offshore wind. It directs its efforts on the durability and long-term strategic perspective of the industry as the nation’s leading opportunity and resource for clean energy in a time of climate crisis.

Ohleth has worked in the offshore wind sector for almost 20 years and holds significant insights into the policy and regulations that affect offshore wind activities at all levels of government. As director of SIOW, she leads the organization in creating strategies and pathways to facilitate the competent and continual development of offshore wind.

“The New Jersey Wind Port is essentially the first purpose-built offshore wind port in the United States that focuses on marshalling or staging for offshore wind,” explained Ohleth.

“In order to minimize the amount of times heavy machinery like cranes are used at sea, for safety, logistical, and cost reasons, it’s really helpful to have an onshore port where a lot of that staging and marshalling can happen,” she said.

“The wind farm components are so large that they cannot be moved on roadways,” she said. “One blade length is as long as a football field and that exceeds any safe or possible transit along the U.S. roadways. Essentially, all work needs to happen port to port.”

Gov. Phil Murphy plans to utilize the wind port to fulfill his Energy Master Plan. The State of New Jersey described the plan as “a strategic vision for the production, distribution, consumption, and conservation of energy.” Goals include achieving 100% clean energy by 2050 and producing 7,500 megawatts of offshore wind energy by 2035.

“We will take full advantage of our world-leading and central geographic location to drive the growth of a new industry right here,” Murphy said at a press conference.

Together with infrastructure development, New Jersey is investing in education to create skilled employees and sustainable jobs for the future. According to Rowan Today, on March 21, U.S. Congressman Donald Norcross presented Rowan University a ceremonial $500,000 check for a federal workforce training grant in hopes of preparing students for the state’s growing wind power industry.

“The grant will fuel workforce training programs designed to fit the needs of wind energy employers, starting in high school up through graduate-level engineering degrees,” the article stated.

While New Jersey continues to accelerate development of offshore wind, land-based wind farms have received little attention. Ohleth provided a simple explanation, “Here, we have a lot of trees, we have a lot of development, so it’s not the best place, really anywhere in the Northeast or Mid-Atlantic, for putting land-based wind farms.

“We just don’t have a lot of open space like they do out West in California or Texas where they can put them on big open fields and there’s a lot of opportunity for wind to pick up speed,” she said. “What we do have is big open space in the ocean.”

Since there are no strong alternatives for utility-scale renewable energy in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, building offshore wind is imperative to meet clean energy goals.

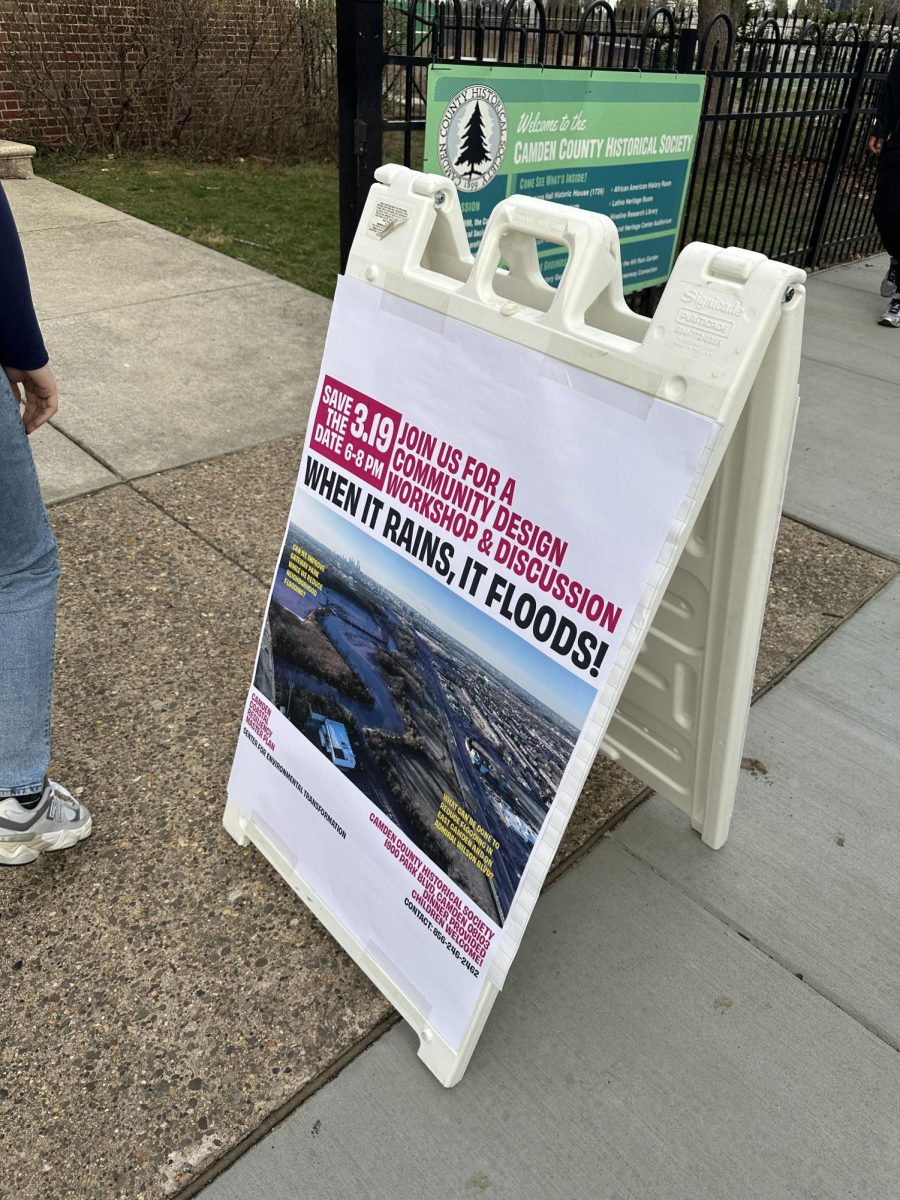

Presently, many cities of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast are rushing to meet energy and emissions goals. Most of the cities import clean power from other states via the grid because they have no other way of producing and delivering clean energy.

“If we want that energy locally sourced and locally produced so that we’re avoiding line losses across long distances like power being developed out West and if we want the economic development opportunities then offshore wind is literally the only solution available at this time,” Ohleth said.

In terms of scale, the Departments of Interior (DOI), Energy (DOE), and Commerce (DOC) announced a shared goal in March to deploy 30 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind in the United States by 2030.

“That would require the buildout of over 2000 wind turbines at their currently deployed rate which is around 15 megawatts per turbine,” explained Ohleth.

“It’s certainly not an easy road but I think we could still meet that target if we continue to stay aggressive on the development of the resource,” she added.

Ohleth indicated three challenges in creating an offshore wind industry at scale.

The first key challenge is the transmission infrastructure at the coast. There are a lot of power plants in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and other states which transmit power to the East Coast.

“However, as you get to the coastal areas, the infrastructure gets more and more fragile. By the time you get all the way out to the coast and the beach cities, you’re looking at the tiny capillaries if you look at the power plants as the beating heart,” Ohleth said.

“Now, we’re flipping the model on its head and we’re trying to put a heartbeat out in the ocean and deliver gigawatts of power into those tiny capillaries. We’re flipping the system backwards and meeting an opportunity to upgrade and have a smarter grid system to be able to accept all that power that is being injected at the coastline.”

The second challenge is the port infrastructure. Ports are intrinsic to offshore wind development but quite scarce in the United States.

“There are not not a lot of available ports because one thing that’s critical to port development is making sure that there’s enough clearance to stand up some of the larger components and take them out to sea,” said Ohleth.

Obstacles like wires, bridges, and poles often prevent port development and expansion due to the sheer size of wind turbine components.

“If you look at the port system in Europe, they have many larger areas and many bigger ports that are available for use than we do here in the United States. It’s something that the offshore wind industry is aggressively seeking solutions for,” she said.

The third challenge is opposition from local stakeholders which includes individuals who live in coastal communities to local fishermen. Some stakeholders voice that building wind turbines would ruin the views of coastal cities and prevent local fishermen from fishing.

Ohleth expressed that their concerns are warranted. Nonetheless, she underlined the adaptability and resourcefulness of fishermen.

“I will say that fishermen are masters at adapting,” she said. “They are currently doing their best to adapt to climate change.”

Many are seeing fish migrate, species dying out, and inclement sailing weather due to the warming climate.

According to Ohleth, the best step forward is to equip stakeholders with proper resources to adapt. In the long term, most know that offshore wind will help their industry and our planet.

“There really is a whole economic ecosystem that gets stood up when you have a very unique and new industry coming to a region,” she said. “Frankly, it’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity for our country and our region to experience.

“We haven’t seen the birth of an industry in quite some time and certainly not one that’s local to New Jersey so, this is why the state is laser-focused on making sure offshore wind happens,” she said.

Alongside many others, Ohleth believes that we are steadily approaching a point in the climate crisis where it might be too late to save the planet.

“We’ve heard some critics say that this is too much too fast and too much too soon,” Ohleth said. “In my estimation—and maybe my perspective is much different because I’ve been doing this for nearly 20 years now—we are way far behind and we are not doing enough quickly enough.

“It needs to be a moonshot,” she added. “It needs to be all hands on deck. We need to be doing everything we can to fight the climate crisis. It’s the most urgent crisis of our time and we have the tools to do it.”