Climate change represents a critical issue that is often discussed in a blanketed manner. Writers express how climate change affects “us” and “our” daily lives. But does it really affect all of us? Does it affect some people more than others? Why should we as individuals care? Is there any hope?

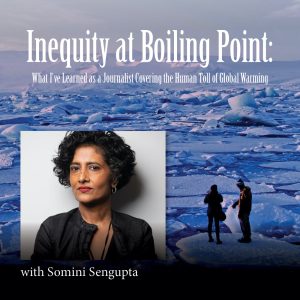

At the 2022 Distinguished Lecture in Global Security hosted by Rowan University on March 29, international climate correspondent Somini Sengupta answered these critical questions by drawing from her experiences and lessons learned while reporting on climate conflicts around the world.

“We need to understand what a hotter planet means for you, for me, for our communities, for our geopolitics, and what can be done about it,” she stated.

Sengupta works as a correspondent for The New York Times and presented the stories of different communities and territories threatened by the effects of climate change. She has previously reported from a Himalayan glacier, Congo River ferry, the streets of Baghdad and Mumbai, and many more locations. Additionally, Sengupta has won a George Polk Award for foreign correspondence and is the author of “The End of Karma: Hope and Fury Among India’s Young,” published by W. W. Norton in March 2016.

Sengupta’s talk, “Inequity at Boiling Point: What I’ve Learned as a Journalist Covering the Human Toll of Global Warming,” specifically focused on the disproportionate effects of climate change based on different components such as class, national origin, economic status, and occupation. She highlighted four fundamental lessons she learned while covering the human toll of climate change.

“Lesson 1: We have already changed the climate of the planet we live on, measurably.

“Lesson 2: Climate change exposes the sharp inequities already in our societies.

“Lesson 3: This is the decade when we can keep the world from getting hotter with exponentially worse climate impacts.

“Lesson 4: While it’s tempting, in the face of such an overwhelming problem, to think that nothing can be done, that the world will become uninhabitable, that’s simply not true.”

Lessons 1 and 2

Lesson 1 involves the acknowledgement and acceptance of the current climate crisis, Sengupta said.

“We must adapt to that fact,” she said. “We must adapt to life on a hotter planet. Where we go from here is up to us.”

The average global temperature is about 1.1°C higher today than it was 150 years ago. This change happened “because we burned a lot of gas and oil in the last 150 years,” Sengupta explained.

“Half of the emissions of greenhouse gasses that are in the atmosphere now have been produced since 1991,” she said.

“The impacts of the warming so far are being felt right now,” Sengupta emphasized. For instance, in 2021, flooding in Germany and Belgium, Hurricane Ida, and extreme cold in the central United States resulted in over $120 billion of damage.

Lesson 2 relates to the irregularly spread consequences of climate change.

“The impact of this climate change is not evenly or fairly spread, not at all,” Sengupta told the audience. “Like the pandemic, climate change exposes the very sharp and different kinds of inequities in different societies.”

The inequities are acknowledged by those closely following the effects of climate change. An Oxfam article about Earth Day 2022 stated, “The richest one percent of the world’s population are responsible for more than twice as much carbon pollution as the three billion people who made up the poorest half of humanity in the last 25 years.”

As a result of climate change, “An estimated 13 million people across Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia have been displaced in search of water and pasture, just in the first quarter of 2022, despite having done little to cause the climate crisis,” the article noted.

Climate Refugees

Tuktoyaktuk, a small Inuvialuit settlement of 950 people located in the Inuvik Region in Canada, is another area that faces disproportionate danger from climate change. North of the Arctic Circle on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, Tuktoyaktuk suffers from increasing coastal erosion due to melting permafrost in sediment layers underneath the settlement.

“There is so much coastal erosion happening there because the permafrost is thawing and so the land that they live on is actually giving way and falling into the ocean,” said Dr. Lauren Kipp of Rowan University’s Department of Environmental Science.

Kipp uses naturally occurring radioactive isotopes to study the chemistry of the ocean. Much of her research takes place in the Arctic and revolves around understanding how rising air and sea temperatures affect interactions between the land and the Arctic Ocean.

“The community that lives there might actually have to relocate their entire town further inland because the coastline is eroding away so quickly as a result of rising sea levels and the thawing of permafrost,” she said. “They might be some of the first climate refugees that might have to move as a result of land loss due to the warming climate.”

Permafrost occurs on land, below land, and below the ocean floor. It consists of gravel, soil, and sand usually connected together by ice. Permafrost commonly forms in areas where temperatures rarely reach above freezing. The mixture of sediment and ice usually remains at or below 32ºF for at least two years.

Kipp described two distinct manifestations of ice in the ground. Water in between sediment particles in the ground can be frozen which leads to permafrost. In some places, massive ice lenses, which look like wedges or triangles of ice, form due to moisture diffusion in soil and rock. They wedge between layers of the ground and grow several inches to feet deep. The thawing of these ice formations leads to massive subsidence and massive slumping.

The community in Tuktoyaktuk lives in areas where it’s mostly the first case of permafrost but there are some ice lenses as well which cause catastrophic collapse.

“The coastal erosion is really high there because sea level rates are high and because the waves are eroding the coast,” Kipp said. “The loss of sea ice allows for bigger waves to happen because the ice isn’t acting as a barrier between the wind and the water. So, you have bigger waves pummeling the coast and causing more erosion and then you also have permafrost thawing causing more erosion. So, you have this kind of double whammy of thermal and physical erosion causing the land to fall into the sea.”

Sengupta noted that lower class laborers also are some who suffer the most from inequities.

“Those who are poor, those who do back-breaking work often outdoors at low wages without health insurance and sick pay, those who are least responsible for the problem, face some of the most acute consequences of climate change,” she said.

Things many take for granted such as stable electricity, air conditioning, and occupational choice, heavily affect lower class individuals and their hardships from climate change. For an agricultural worker, severe heat and drought prevent income and food provisions due to crop failures.

“Decisions made in the past often affect the climate impacts that are felt today,” Sengupta said.

In addition, “In some places in the United States, redlining can place a city’s black residents at far greater risk of living in a neighborhood with fewer trees—where hot days feel even hotter,” she said.

Native Americans that have been relocated face greater climate risk as well, Sengupta said.

Lesson 3

Sengupta’s third lesson served as a call to action regarding the climate crisis. Sengupta urgently reiterated that substantially reducing our carbon footprint needed to happen within this decade.

“The baseline temperature is projected to be, at least, 1.5°C hotter by 2040,” she said. “We’ve gotta adapt fast to a world that’s hotter, to a world with more extreme weather. This requires changing where we live, how we design cities, how we grow food, and how we build things. Many things are being done, but just not at the scale and at the pace that’s necessary.”

Kipp added, “I don’t know if the 1.5°C goal is super achievable at this point but, certainly 1.7°C is better than 2°C or 2°C is still better than 2.5°C. I think that there’s still time to make changes that are going to have a measurable impact.”

To actively combat the climate crisis, Sengupta listed measures governing bodies could implement to minimize damage and loss from extreme weather. Local governments can establish early warning systems to alert people of bad weather, conserve water, restore floodplains, build oyster reefs to protect coastal communities, and paint sidewalks white to cool down city blocks.

“Beyond that 1.5°C threshold, according to scientific consensus, the impacts are exponentially worse,” said Sengupta.

To avert a worse climate crisis, scientists believe we have to cut greenhouse gas emissions by nearly half by 2030, Sengupta explained.

Is it possible?

The answer is yes, but with a caveat. We know how to produce energy without burning oil, gas, or coal. Wind turbines represent one method of producing sustainable energy.

According to Sengupta, “One study concluded that the 27 countries of Europe could reduce its dependence on Russian gas by two-thirds by 2025 if it really expands renewable energy and takes energy efficiency measures.

“The price of renewable energy has dropped really fast,” she notes. “Same with transit, the world knows how to get people around, by and large, without burning gas.”

Sengupta highlighted the importance of establishing a sustainable food production infrastructure as well.

To reduce emissions from food production, “We can stop mowing down forests to grow food and we can do one more thing,” she said. “We can stop wasting food, that is arguably the simplest and most common sense way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“In the United States, one-third of the food we grow is not eaten,” Sengupta said. “It’s wasted. That’s wasted soil, water, fertilizers, energy to plow the field, energy to transport all those tomatoes and avocados, energy to package them, and when all of that ends up in the trash, in landfills, what does it produce? It produces methane. A super potent greenhouse gas.”

Meanwhile, the main challenge that stands in the way of a sustainable future is the fossil fuel industry.

According to the Oxfam article, fossil fuel companies receive $15 billion annually in federal subsidies paid for by taxpayers. Many attribute government assistance and climate denial as the primary agents powering the fossil fuel industry.

“Shifting the global economy away from fossil fuels is disruptive, it’s disruptive to the incumbents,” said Sengupta.

Due to recent world events such as Russia’s war with Ukraine, “Oil and gas production are at record levels in an era of increasing climate change,” Sengupta said.

“This wartime enthusiasm for gas could very well lock in more fossil fuel infrastructure for a long time.”

Lesson 4

Lesson 4 addressed a common question connected to the climate crisis: Are we doomed?

Sengupta does not think so.

“There’s actually very little evidence to support the hypothesis that we’re doomed,” she said. “The future is not foretold.”

Kipp echoed Sengupta’s stance.

“There is no such thing as too late because anything we can do now will reduce the harmful effects in the future,” she said. “We’ve already passed a certain point where we’re going to see certain effects, but if we can reduce our impact from here on out then those effects won’t be as bad as they could be.”

Sengupta added: “The future depends on a series of human decisions that are being made right now—political decisions, financial decisions, social decisions being made right now.”

Ordinary people using their votes, lawyers taking fossil fuel companies to court, new architecture, and retrofitting old buildings illustrate some ways to address the overwhelming crisis.

“I think the most powerful thing individuals can do is use their right to vote,” Kipp said. “They can vote for government officials that see climate as a priority and that will enact legislation to combat climate change, but also acknowledge the fact that there is a climate-justice issue and that this is not a problem that is fairly distributed around the world.”

The 2022 Distinguished Lecture in Global Security was sponsored by Rowan University’s International Studies, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Hollybush Institute for Global Peace and Security, Department of Journalism, and Department of Geography, Planning, and Sustainability. It was funded by a UISFL grant from the U.S. Department of Education.