A few miles from New Jersey’s southernmost tip, the Cohanzick Nature Reserve is an important cultural center and meeting place for South Jersey’s Indigenous community. It also serves as a testament to the sustainable practices that have helped the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape people and other surrounding native communities for generations.

Aside from the former church’s building, parking lot, and an outdoor wooden pavilion, most of the land at Cohanzick is untouched forest.

There are plans to incorporate a garden and efforts to clear walking trails throughout the property, although most of the work on the reserve is related to preservation so that future generations can also enjoy the land and embrace their culture, avoiding what can be seen as the exploitation of the land.

“Everything we do affects every generation in front of us, we believe that we have to be responsible for everything… the earth, the land, and the water, because it’s not just for us and we don’t own it,” said Tyrese Gould Jacinto, president and CEO of NAAC which owns the property. “These things are gifts, and we are here as gifts, so therefore we have to take care of it because it’s not just us, it’s our children and grandchildren into the next seven generations.”

The reserve was established in 2023 on the 63-acre site of a former church in Quinton Township.

The site’s purchase was a collaborative effort between the Native American Advancement Corporation (NAAC), the New Jersey Conservation Foundation, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s (NJDEP) Green Acres Program, and The Nature Conservancy.

The name Cohanzick was brought back into popularity in 2007 after a reclamation ceremony for 28 acres of sacred land repatriated to the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape people. The term roughly translates to “that which was taken out” and references lands lost by previous generations through colonialism and land deals made by settlers in the area.

The conservationist philosophy that Jacinto describes is called seventh-generation thinking or seventh-generation sustainability. This is a philosophy that is often associated with or attributed to indigenous groups in the area. Many of the ongoing projects at Cohanzick adhere to this philosophy.

However, some of the ideas often associated with mainstream nature conservation are at odds with the traditional lifestyles and practices of indigenous groups.

A few indigenous traditions, like raised bed gardening and foraging for berries and mushrooms, have become commonplace among home gardens and high-end restaurants across the country. But the reality of practicing some of these traditions for Jacinto and her community is at odds with the state’s idea of conservation.

“So you want to preserve the forest, which is great, but then it makes you look like you can’t use it because of conservation efforts,” Jacinto said. “Even in New Jersey, they don’t let you do foraging, which is crazy.

“Conservation also has its downfall, and what happens with our communities or communities just like ours, we become collateral damage,” she added. “We are in the middle because we don’t want to exploit and we don’t want to conserve, but we want to live one with.”

Some of the more culturally oriented traditional practices were on full display during a pre-Easter “EggStravaganza” celebration held at the reserve in mid-April.

Part of the celebration featured arborist John Barry helping the younger community members to gather wood from a white pine tree that had fallen during a recent storm to make a traditional staff for the spring solstice, which the Easter Holiday usually lines up with.

Barry is the founding director of the Cohanzick Climate Corps and the U.S. Department of Labor’s Registered and Approved Arborist Apprenticeship program. Barry is a Rutgers University-certified public grounds manager and is accredited by the International Society for Arboriculture (ISA), where he is an ISA-certified arborist.

Barry has been involved with the NAAC for the past 15 years and credits his family of farmers and foresters for sparking his interest in the field.

“My grandfather used to come in and clear each section of the forest, and the burnt material from the clearing would be organic fertilizer for the soil,” Barry said.

The practice, known as prescribed burning, has been used by indigenous groups in the area for centuries to maintain the forest and facilitate travel between wooded areas. Barry later added that it’s become more common in the last few years for people to spend a lot of money on the charred material from controlled burns to get a better pH value in their soil.

Aiding Barry in some of the more laborious preparations for the April event was Sean Torres, the 24-year-old grandson of former Chief Mark “Quiet Hawk” Gould. Torres has served as the field manager for Cohanzick for the past year and a half since it opened, and plans on pursuing a future career in the arborist industry.

One of his proudest achievements since the work at Cohanzick began has been clearing and reopening horse trails on the property that haven’t been touched since horses were a primary mode of transportation in the area.

(Photo courtesy of the Cohanzick Nature Reserve)

“This is something that I love to do. I come out here during my free time when I’m not even on the clock, just to get peace of mind,” Torres said.

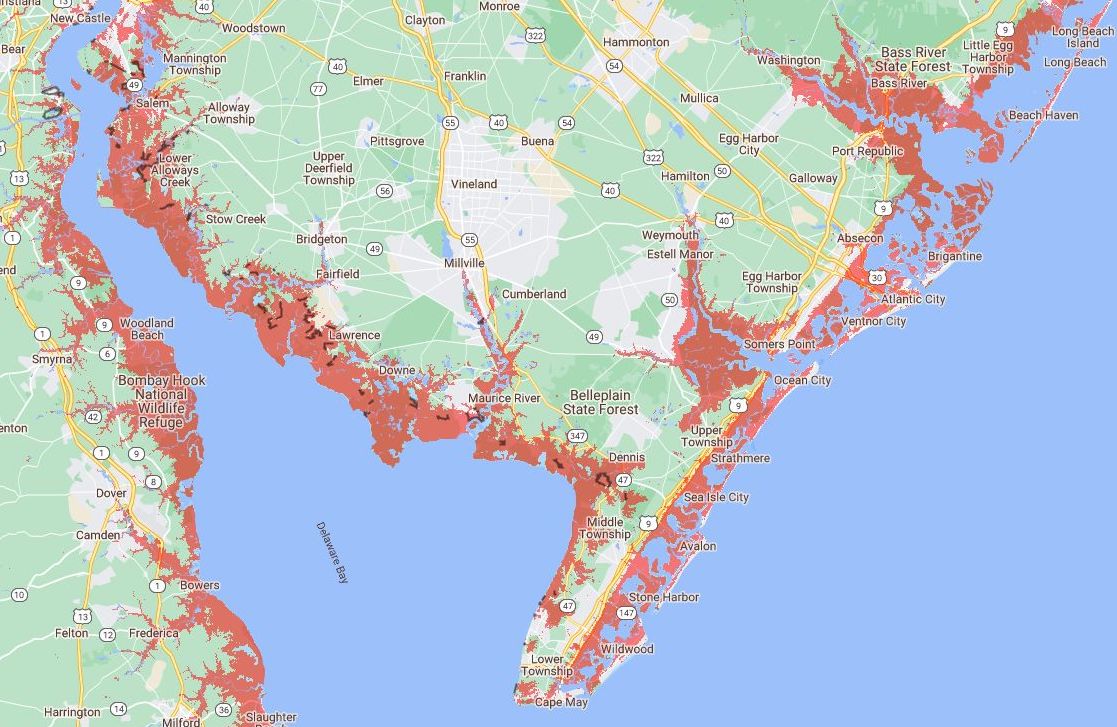

Despite the increase in resources afforded to the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenapi Tribal Nation through the acquisition of the Cohanzick Reserve property and other funding awards for their Cohanzick Community Forestry initiative, the community has faced a few challenges in living one with nature in the face of climate change.

Certain weather conditions, particularly extreme heat in the summer months, threaten events like camping retreats and other primarily outdoor cultural activities. The community’s historic fishing practice has also been threatened in recent years by a combination of increased regulations on fishing by the state and a decrease in publicly available fishing waters due to the privatization of lands in the southern tip of the state.

Despite the challenges that a changing climate may bring, Lia Gould, who manages most of the tribe’s youth programming, is committed to always finding ways to embrace their culture, especially when it comes to their community’s kids. Gould is the younger sister of NAAC CEO Tyrese Gould Jacinto.

“We’re always going to find a way to make it happen, whether it’s us camping inside a building or setting up canopies if it’s raining so that we can all still commune together,” she said. “But a lot of what we’ve seen recently is that a lot of the places our ancestors fish are all bought up and private property now, so it’s a little heartbreaking to see the things where you hear these stories from your elders and to not be able to follow through with that.”

Gould organized the April Event and many of the other tribal meetings and celebrations with her husband Ty “Dancing Wolf” Ellis, who manages most of the adolescent and teenage tribal youth activities. Together, the two of them also head the Lenapehoking Reestablishment Project, which focuses on the promotion of Indigenous Education, Arts, and Support.

“I think the toughest part is we can’t control Mother Earth, right? So all we can do is grow with it,” said Ellis.

Last August, an outdoor camping retreat had to be moved indoors because the weather outside was too hot for the kids to camp in. Temperatures reached over 100 degrees at times during the planned weekend.

“For me, I’m also an air conditioner kid,” Ellis joked. “ I think there is a decent blend of modern living and our traditional ways that we’re beginning to see, and we’re acting accordingly. It’s good to have this [building] because we can’t control the weather. We can’t control any of this, and I think human beings have that habit of thinking that we can.”