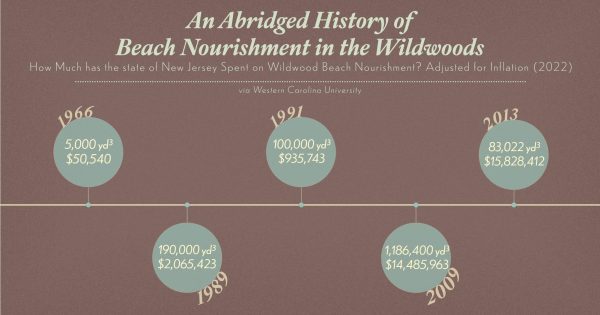

With growing concerns over beach erosion, places like Wildwood in Cape May County have spent millions of dollars on beach nourishment and replenishment, a strategy that has now become a point of contention in New Jersey. An examination of climate change, tourism, and beach preservation in general shows exactly why that is.

In May 2024, North Wildwood announced a $10 million Emergency Beach Nourishment Dredging Project, created as an interim agreement between the town and the state of New Jersey after strong contention over beach nourishment just that February, that would bring in 350,000 cubic yards of sand to North Wildwood beaches. Unfortunately, that sand is not permanent.

“If a storm comes in, it’s taking away some of that sand. And if you have erosion problems, that sand’s not going to come back,” said James Shope, applied climatologist at the Rutgers Climate and Energy Institute. “Communities will invest, you know, millions of dollars into putting sand on the beach and building up a dune, and one storm cycle later it could be, not always, but it could be just completely removed.”

Climate change has severely affected natural disasters, such as coastal storms. While storms may not occur more frequently, it is believed that they may become stronger and produce more rain. Shope said that hurricanes are “fueled” by warm water and humid air, and global warming naturally warms the ocean, so moving forward, it is likely for these storms to have stronger “fuel.” As the atmosphere warms, its capacity to hold water vapor also increases, meaning that it can hold more water which will later become rain.

So why continue with beach nourishment if storms are only getting stronger and with that, the chances of furthering erosion?

Beach nourishment has sustained the Jersey Shore for over 90 years, beginning in Cape May in 1989, so it’s not an entirely new practice, and is actually carried out every few years.

There are positives to beach nourishment as well. Primarily, it is a good preventative measure for flooding. A wider shore means more sand to move with the currents, which is good protection against flooding and further erosion. This is important in shore towns where tidal-flooding, or floods caused not by storms but by exceptional high tides, is becoming more and more prevalent in places like Wildwood.

Mayor of North Wildwood, Patrick Rosenello, said that beach nourishment is a temporary fix, and that it is not a permanent solution. He said that the sand is “sacrificial.” However, it is not the only protective measure the town has taken. The town’s major shore protections include a rock revetment, or seawall, that they plan to expand by a quarter mile and bulkheads which keep the land and the bay separated. Rosenello stated that the towns on the shore typically have a combination of hard structures – such as the bulkheads and seawall – and soft structures, like dunes and beach nourishment, in order to preserve the shorelines.

Additionally, beach nourishment proves to be good for the economy.

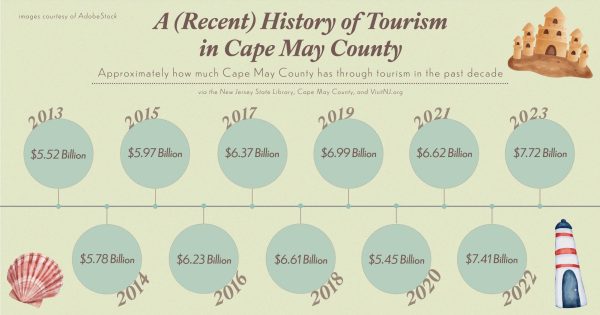

Billions of dollars in the New Jersey economy are generated from tourism, with the state seeing $78.3 billion in economic activity, and the same extends to Cape May County. In 2023, the Wildwoods saw over $10.51 million generated in tourism tax revenue, while Cape May County overall made $7.7 billion in tourism.

The county reports that it saw more than 11 million tourists in 2023, an increase from 2022, and over two million more visitors than the state’s actual population. These are not insignificant numbers and it is only natural for these towns to be worried about a sudden loss of revenue, especially one as significant as this.

When North Wildwood announced their Emergency Beach Nourishment Dredging Project, it was specifically stated that it would be carried out “just in time for the summer tourism season.” The connection between beach replenishment and tourism is not a fickle one.

Rosenello additionally aired out a grievance with the NJ Department of Environmental Protection which advocated for retreating from the Jersey Shore due to a projected five-foot sea level rise by 2100. Instead, Rosenello believes that the energy should be redirected towards working on ways to adapt to climate change.

“It is really, to me, an illogical frame of thought,” Rosenello said, pointing out that it would be illogical to follow that line of thinking into abandoning Miami, New York, or other major cities. “Do we have to adapt and change? Yes, absolutely. Do you have to make sure things are resilient? Absolutely. When you live at the Jersey Shore, you know that better than anyone.”

Despite the state’s efforts, beach nourishment remains a point of contention in terms of both government and climate. The shore towns need help and protection from the state, but the state is not able to act as quickly or provide as much assistance as these towns would like. Additionally, while these beach replenishments help protect the towns from flooding, millions of dollars are being spent and over-invested pon sand shipments that may be gone within one storm cycle as tropical storms become more powerful.

Other proposed methods of preventing beach erosion, such as sand groins, which are no longer permitted on the Jersey Shore, are meant to trap sand on the beach. This strategy comes with negatives as well. Shope stated that while the sand does get trapped, other beach towns are no longer receiving the sand that would have traveled downstream, worsening their own coastal erosion.

Although the tourism industry has greatly helped New Jersey and the Jersey Shore’s economy, tourism, combined with climate change, both uniquely affect the state’s coastal town in ways that are difficult to navigate.