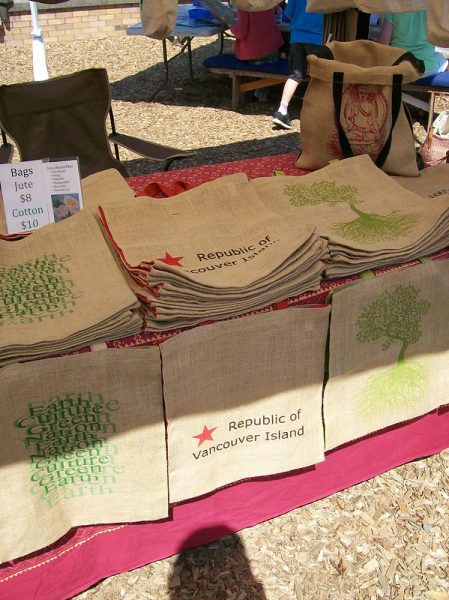

In May 2022, New Jersey became one of 12 states to ban the use of single use plastic bags in retail and grocery stores. Taking their place were reusable carryout bags. The state announced and celebrated this ban as a monumental step towards sustainability, but research shows otherwise after two years of living this way.

The Institute for Energy Research (IER) reported that 90% of reusable bags bought in New Jersey were used only two or three times before being forgotten about, when they should be used at least 16 times to make an impact.

The IER also reported that the “total number of plastic bags did go down by more than 60 percent to 894 million bags, [but] the alternative bags ended up having a much larger carbon footprint with the state’s consumption of plastic bags spiking by a factor of nearly three.”

Freedonia Custom Research also reported that plastic consumption in New Jersey nearly tripled after the single-use-plastic-bag ban went into effect, jumping from 53 million pounds pre-ban to 151 million pounds post-ban.

The issues with non-woven polypropylene bags, the kind of large, reusable bags you see in your local grocery store, lie in their production, as they “consume over 15 times more plastic and generate more than five times the amount of GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions during production per bag than polyethylene plastic bags,” according to Freedonia Custom Research.

Reusable bags are defined by the state of New Jersey as made of “polypropylene fabric, PET non-woven fabric, nylon, cloth, hemp product, or other washable fabric, and has stitched handles (either thread or ultrasonic), and is designed and manufactured for at least 125 reuses.” Bags with ultrasonic stitching appear to be seamless in their structure, like the bags you see at some convenience stores and grocery stores.

Professor of chemical engineering at Rowan University Joe Stanzione has spent the last 15 years learning and teaching the science of polymers, plastics, coatings, adhesives, and composite materials. Stanzione explained that single use plastic bags are not made to last, and as a society people got accustomed to this mindset of using something once and discarding it. This mindset stuck with people in the transition to using reusable, non-woven polypropylene bags, such as the ones sold in grocery stores.

“So these bags are a lot thicker, oftentimes made out of materials that are even harder to recycle than even those single-use plastic bags,” Stanzione said, “but they’re intentionally designed this way to be more durable, to be thicker, so that it incentivizes us to try to reuse them.”

Although the obvious purpose of these bags is that they are meant to be used more than once, many end up in a stockpile in a kitchen cabinet.

“There’s many people in society that have treated these almost just like single-use plastics,” Stanzione said. “Right now, you’re putting more material into the environment, potentially more into the landfills. These are not recyclable, in the normal sense, they don’t have little triangles on them that tell you that this is a certain type of plastic.”

Stanzione also explained that designing bags that are more biodegradable or more easily recyclable may not be the final, magical solution to this issue.

“It’s also the mindset of the consumer, right?” he said. “Can we do a better job? Yeah, with educating the community on reasons why they should care about using better bags, and developing a better system for maybe the collection of these bags when people have a stockpile of them now, and they don’t need to use all of them anymore.”

One of the alternatives to plastic Stanzione touched on was hemp-fiber-derived bags. Hemp could result in a durable, recyclable reusable bag. Some of the positives of hemp include biodegradability, compostability, renewability, and its low carbon footprint.

According to the materials manufacturer EuroPlas, hemp bioplastic has been gaining interest as an alternative to plastic materials used in products such as bags. Hemp bioplastic, according to EuroPlas, is “a type of biodegradable plastic made from hemp fibers, which has a sufficiently high cellulose concentration in manufacturing polymers. Specifically, it is made of lipids and cellulose found in the stalk and seeds of hemp plants.”

The production of hemp bioplastics and their production are much more energy efficient compared to traditional plastic because the process uses lower temperatures and less pressure, which requires less energy overall. Additionally, hemp bioplastics can biodegrade in six months to a year in the right conditions. Traditional plastic can take 20 to 500 years to biodegrade, depending on the environmental conditions.

Stanzione noted: “They’re domestically sourced [and] that could potentially make really nice, durable bags, and that when they are thrown away, or if they were properly recycled under a certain environmental condition, they could be broken down into benign chemicals, or they could be easily reprocessable.”

Impact of the pandemic

Nandini Checko is the project director for the Association of New Jersey Environmental Commissions and a member of the Governor’s Plastics Advisory Council. Checko also played a part in getting the plastics law passed.

Checko explained that the Covid-19 pandemic greatly impacted the mass use and production of reusable bags in the state with the rise of groceries being delivered to homes. In response, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) decided to allow ultrasonic stitch bags, believing this strategy would strengthen reusable bags and lead to them being used multiple times.

Ultrasonic stitch bags “are the thinner bags that act like reusable bags because they technically fit the definition of multiple uses,” Checko said. “It could be sanitized, could be washed, etc, but from a manufacturing standpoint, they can be mass produced at a much faster pace and cheaper price point. And the pandemic happened, and then there was a need for more bags, and then the manufacturers kind of came in. They’re very clever that way.”

When the law was initially passed, the NJDEP tried to have an air-tight definition of what classified as a reusable bag, and “there wasn’t a lot of awareness” regarding how the public thinks about and consumes plastic, Checko said.

Checko explained that the overconsumption of reusable bags has been an “unintended consequence of the law” and that the answer to this issue is educating the public.

“So the intention of the law was to bring awareness for the amount of plastics in our life, and also to to help towards waste reduction and over consumption,” she said. “But there was a lot in this bill as the first step of education.”

While the law may leave room for improvements, Checko emphasized the dangers of plastic and the importance of reducing plastic waste. For example, Checko pointed out the microplastics found in water bottles, plastics breaking through the blood brain barrier in fetuses, and plastic containing endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Alternative uses of reusable bags

In addition to using hemp bags, there are options for people who feel they have an unnecessary amount of reusable bags. For example, the Food Bank of South Jersey (FBSJ), which services Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Salem counties, accepts donations of reusable bags. Food banks and pantries were granted a six-month extension to use single-use plastic when the ban was enforced.

The Food Bank of South Jersey acts as a wholesale warehouse to over 300 partners throughout South Jersey. Local pantries collect food items from FBSJ to distribute to those in need in their surrounding areas.

Kristin DeJesus, Senior Manager of Food Sourcing at FBSJ, explained that although they are happy to be reducing waste, there was a convenience and ease of having plastic bags that was taken away when the ban was put into effect.

“It was much easier for retailers, who had millions of them, to just break off a few 100 for the local pantry every month and not really think twice about it, whereas with the institution of this new bag ban and the use of reusable bags, they’re more costly, and so our pantries aren’t able to source the reusable bags, nor were they prepared to fund the reusable bags,” said DeJesus.

To aid their members, FBSJ launched a campaign to collect reusable bags at 22 collection sites in libraries across their four-county service area.

In preparation of the ban, the Food Bank tried to communicate with the public that they would need to bring their own bags when visiting their partnered locations. Ultimately, the pantries needed to collect and keep bags for patrons. Initially New Jersey Clean Communities donated around 100,000 bags to the Food Bank.

“So they did make a concerted effort to support the state’s food banks during the transition initially, but that has dropped off,” DeJesus said. “So now it’s how do we prevent creating more waste with the reusable bags, right? By getting them donated or to proper recycle centers.”

The biggest challenge facing FBSJ right now is how to fund the continual cycle of purchasing reusable bags.

“So the reusable bags are just significantly priced higher. Where you might have gotten a plastic bag for a couple of cents, you’re now 15 cents plus for a reusable bag, and for a pantry who’s serving 500 people on a weekly basis or a bi weekly basis, it just becomes a lot,” said DeJesus.

Over two years living in a plastic-free state, and many questions still remain for institutions like the Food Bank of South Jersey.

“I think that’s what as a network we’re still kind of working through, is where does the funding come from? Who’s responsible for buying the bags? Is it the food bank? The larger organization? Is it the pantries? How are we getting them funding?” said DeJesus.