Dozens of organizations are leading the effort to protect New Jersey’s watersheds today. One of the most influential is the Americorps Watershed Program, administered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Water Monitoring and Standards.

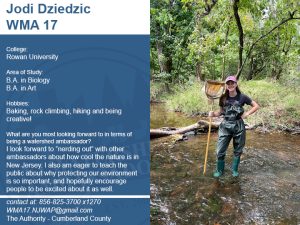

Each year, the program selects about 20 members to become ambassadors who facilitate the ambitions of the Americorps program. One of the 2021-2022 ambassadors is Jodi Dziedzic, who is responsible for watershed management area 17 in the lower Delaware region, which covers parts of Atlantic and Gloucester counties and a majority of Salem and Cumberland counties. Her position with Americorps is hosted by the Cumberland County Utilities Authority.

Dziedzic graduated from Rowan University in Spring of 2021 with a Bachelor of Science in Biology and a Bachelors of Art in Art Studies. Dziedzic is one of many among the Americorps Watershed Ambassadors who has gone above and beyond to bring attention to water issues within her home state.

“Right after graduation, I was looking for a position to gain experience working for the state, so I got a seasonal job at Parvin State Park,” Dziedzic recounts. “From there, I knew my next step would need to be journeying further into environmental work within the NJDEP, so when I found out about the watershed ambassador program, I knew it was a great opportunity.”

Watersheds are areas of land that drain into a body of water, such as a lake, stream, or bay. No matter where you live in New Jersey, all land drains into a designated watershed. Watersheds are essential for clean water sources in the water bodies they surround. New Jersey has up to 20 different watershed management areas or WMAs.

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and its Americorps Watershed Program have been preserving these watersheds for the last 20 years. The program currently has over 400 members.

“The goals of the program are to promote watershed stewardship through education and direct community involvement, and to monitor stream health through performing visual and biological assessments,” said Caryn Shinske, spokesperson for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. The program focuses on the most densely populated parts of South Jersey, Shinske said.

Dziedzic explained that the work of a Watershed Ambassador involves visiting the watershed area and assessing “visual characteristics such as algae growth, litter concentration, and forms of habitats present.” These phenomena are observed to generate data on important factors that can shift the quality of a watershed.

Dziedzic noted that many residents are unaware of their everyday impact on watersheds.

“A major issue I personally have seen is nonpoint source pollution in the form of litter concentration,” Dziedzic said. Nonpoint source pollution is also known as “people pollution,” or pollution that comes from several different sources instead of one.

The Environment Protection Agency states nonpoint pollution “is caused by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground. As the runoff moves, it picks up and carries away natural and human-made pollutants, finally depositing them into lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters and ground waters.”

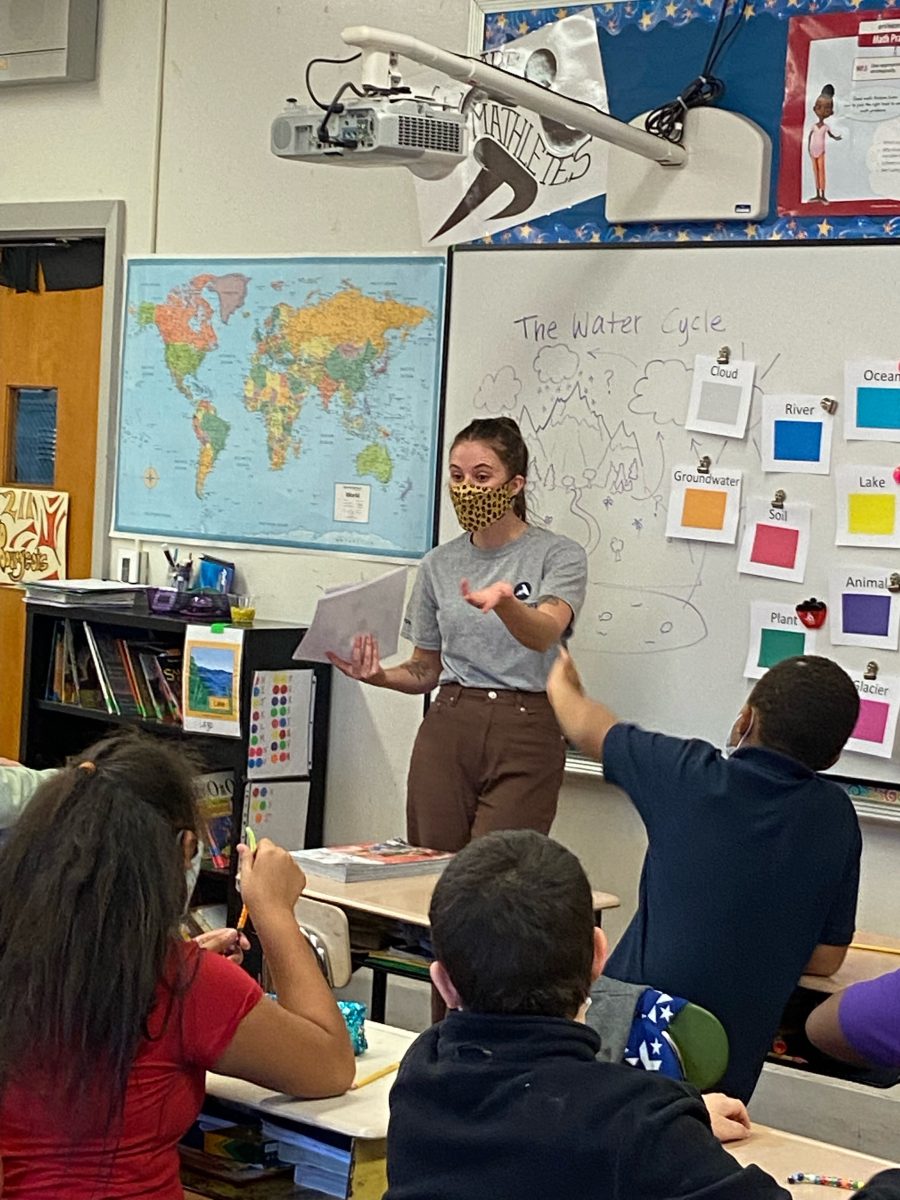

Shinske said a very large part of the Watershed Ambassador’s work involves going out and educating the public about these water sources and the public’s impact on them.

“Ambassadors spend much of their time performing outreach and education, explaining the differences between point source and nonpoint source pollution,” she said. “They impress upon their audiences that whatever we do on our land will affect our water quality. Pollution that makes its way into our local creeks and streams, flowing through our neighborhood parks and sometimes right through our backyards, will eventually work its way downstream to our larger rivers, bays, and eventually to oceans.”

The Inner Coastal Plain of New Jersey is a mostly flat area of the state that is “underlain by sands and gravels of Creataceous origin (about 100,000,000 years old) with meandering rivers which drain to Raritan or the Delaware River,” according to the Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River and Its Tributaries website. The inner coastal plain includes Middlesex, Monmouth, Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Salem counties. These areas are known for their fertile soil, which is why most farms are located in South Jersey and water quality issues are prominent in the area.

South Jersey’s rural and farm-focused residents will see that their pollutants differ from those in urbanized areas. Fertilizers, pesticides, and animal waste all run into rural watersheds, which pollutes the watersheds, water sources, and water quality.

South Jersey Water Savers is an educational campaign that is made up of nine other organizations that share a goal of protecting Kirkwood-Cohansey Aquifer, South Jersey’s main water source. The program is part of the Delaware River Watershed Initiative, which was organized to protect rivers and streams that supply drinking water to the region. According to the South Jersey Water Savers website, “Pollution such as pet-waste, pesticides, and herbicides, are the number one cause of nonpoint source pollution in South Jersey.”

Impact of Climate Change

In an essay by Daniel Altieri of Swarthmore College called The Effects of Overpopulation on Water Resources and Water Security, an increasing population damages the water resources around it. Altieri explains how a rise in population increases watershed pollution and the amount of human and pet waste that ends up in the waterways.

An increase in population also means higher demand for resources. Access to these resources is impacted by climate change effects such as droughts and flooding, which can lead to water scarcity and national security issues. Climate change effects such as variations in temperature also affect resources like crops and vegetation.

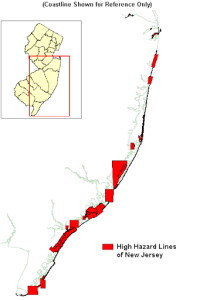

Flooding, including increased flooding caused by climate change, is a major issue in New Jersey. According to the NOAA Office for Coastal Management, New Jersey’s shore residence has a coastal population of about 7.15 million people, which makes for 7.15 million people affected by flooding who depend on watersheds for doing dishes, showering, watering their lawns and most importantly drinking water. The image and caption below were made by the NJDEP Bureau of GIS, illustrating which parts of the state are more likely to be in hazardous zones when major coastal flooding occurs.

Major coastal flooding also affects groundwater discharge. Groundwater discharge occurs naturally, and is simply the movement of water from underneath the ground up to the surface. Climate change influences the volume and distribution of water, which is commonly seen through changes in weather patterns and temperatures. Dziedzic and other Watershed Ambassadors measure variables like “sediment deposition, pool substrate characterization, bank stability, and riparian vegetative zone width,” which are factors directly related to watersheds altered by climate change.

Changes in water discharge can have a significant domino effect on watersheds. When too much water discharge occurs, it often has no area in which to drain. The flooding causes a runoff of contaminants and pushes pollutants and more sediments into the watershed itself. With so many different ways pollution can be pushed into these watersheds due to water discharge, it is unknown what other materials are being sent into the watersheds.

Dziedzic suggests that, if people feel helpless in the face of environmental problems such as these, you can start small.

“Get together with a few friends, coworkers, classmates or neighbors and just pick up some trash at a local park or your neighborhood,” she said. Local organizations like a Green Team, the local environmental commission, or your local municipal or county Clean Communities Coordinator also can coordinate cleanups.

“Oftentimes these folks might already have something planned for the future, or they may be willing to take a suggestion on an area they can organize a cleanup,” she said. “It is also fun to get involved in educating children on why it is important not to litter, and how pollution like trash affects our water.”

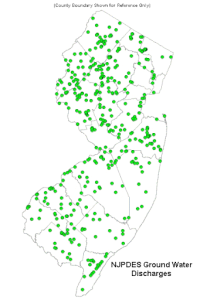

The graphic posted here, provided by the NJDEP Bureau of GIS, presents each location of the recorded and approved discharge areas for certain discharges.

Shinske agreed local action is important and noted that “rain barrel workshops, litter cleanups, tree plantings, rain garden maintenance, and installation, Bioblitz surveys, stream monitoring workshops, are just some of the ways in which ambassadors engage with communities in stewardship.” They have also participated in horseshoe crab flipping to return them to the water with the ReTurn the Favor program, shell bagging with the American Littoral Society, osprey nest maintenance, seal monitoring, plankton trawling events, microplastic sampling, and amphibian road crossing assistance.

Dziedzic said the act of coming together as a community to clean the local environment can have a significant effect.

“I have also learned how powerful and fulfilling it can be to come together and work to make a difference by cleaning up our environment,” she said.