For decades, Camden’s Waterfront South neighborhood has shouldered the environmental and health impacts of its industrial past. Once a manufacturing hub, the area now contends with lasting pollution that affects the air, soil, and water.

These conditions have earned it a reputation as one of the most environmentally overburdened neighborhoods in the city, where residents face elevated risks of respiratory illness and other chronic health issues linked to long-term exposure.

The sources of pollution in Waterfront South are varied and deeply embedded in the area’s landscape. In addition to aging industrial facilities and numerous Brownfield sites that continue to release harmful substances into the environment, the community is also impacted by strong odors from a nearby wastewater treatment plant.

Heavy truck traffic, which moves constantly through local streets, contributes to air pollution, along with emissions from a major highway bordering the neighborhood.

This convergence of industrial activity, transportation infrastructure, and legacy contamination creates a dense, persistent layer of environmental stress that disproportionately affects those who live there.

But on a rainy Friday afternoon this April, change took root—literally.

On April 11, more than 50 volunteers gathered at Liney Ditch Park, a green sliver tucked inside Waterfront South, for a community tree planting and park cleanup. Spearheaded by the New Jersey Tree Foundation, Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority, and Rowan University Planning Studio, the effort brought together local residents and volunteers from the region to take direct action against pollution and climate impacts in their neighborhood.

With umbrellas in hand and boots in the mud, volunteers planted 17 native trees, including Yellowwood, Hawthorn, Dogwood, and Black Locust—species known for their ability to trap pollutants and cool surrounding areas.

Simultaneously, Rowan students led a park cleanup, removing microplastics and discarded trash that often clogs storm drains and degrade urban ecosystems.

“You can feel the difference as soon as you cross the train tracks,” said Rowan student Vignan Ganji. “As soon as you enter Liney Ditch Park, breathing becomes just a little bit easier.”

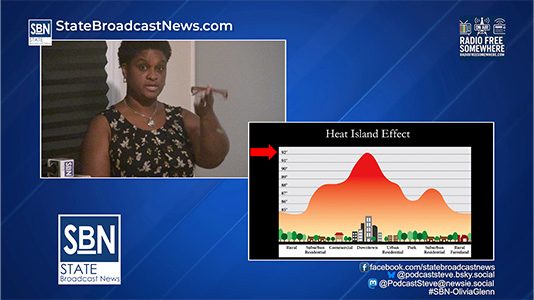

That feeling isn’t just perception—it’s science. Trees are among the most effective tools cities can use to fight the urban heat island effect, where asphalt and concrete trap heat and raise temperatures in city centers compared to rural surroundings. This increase in temperature can worsen respiratory conditions, heighten the risk of heat exhaustion, and even become deadly. Extreme heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the U.S., and urban areas are warming at an alarming rate of 0.33 degrees Celsius per decade.

In Camden, where many residents already face systemic environmental and economic challenges, affordable solutions like urban greening can make a significant impact. But often, air quality is treated like an invisible issue.

“People perceive it as something on the back burner,” said local resident Jenise Rolle. “How do we tie it to everyday life? How do we relate air quality so it saves the city money?”

One way is through tools like i-Tree, a program developed by the U.S. Forest Service. Using data from the EPA’s Environmental Benefits Mapping and Analysis Program, i-Tree can calculate the environmental and economic impact of trees.

According to the New Jersey Tree Foundation, the 17 trees planted last week are projected to intercept over 28,000 gallons of stormwater and remove 65 pounds of air pollutants over the next 20 years.

These small but meaningful steps are planting the seeds of long-term change. As Dr. Seuss wrote in The Lorax, “It’s not about what it is. It’s about what it can become.”

Note: Vin Palmieri is a student at Rowan University. This service-learning project was partially funded through an environmental education grant from the U.S. EPA, awarded to Rowan University.