Earth has already experienced five mass extinctions over the past 440 million years, each wiping out a vast portion of life. We are now witnessing the Sixth Mass Extinction, with predictions that up to 1 million species could vanish.

Unlike previous extinctions triggered by natural forces such as asteroid impacts or massive volcanic eruptions, this one is largely driven by human activity—deforestation, pollution, climate change, and habitat loss. Humans have evolved into a “global super predator,” not only exploiting apex predators but also encroaching on natural habitats and disrupting food chains.

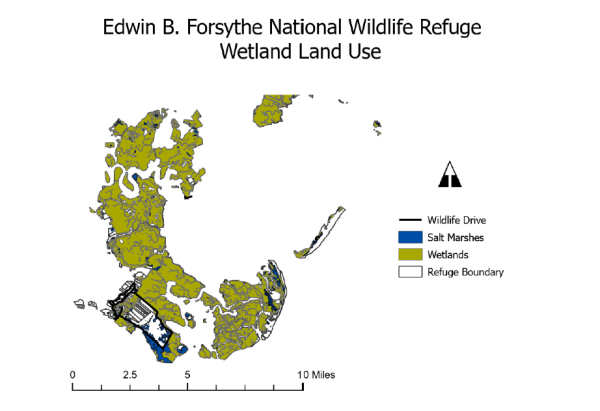

This global ecosystem loss is visible in places like South Jersey, where salt marshes are disappearing at an alarming rate.

These wetlands are among the most valuable ecosystems on the planet, offering critical services such as protecting shorelines from storms, filtering pollutants from water, storing carbon, and providing essential habitat for a wide range of wildlife.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service found that about 70,000 of the 200,000 acres of salt marshes in New Jersey are degraded.

As these habitats vanish, so do the species that rely on them, leading to a decline in local biodiversity and the potential extinction of an entire ecosystem, a clear example of the ongoing Sixth Mass Extinction.

At the heart of these vital wetlands is Spartina, or smooth cordgrass, a humble but powerful plant that acts as the glue holding the salt marsh wetland ecosystem together.

Found along tidal shores, Spartina plays a critical role in protecting these fragile habitats by reducing coastal erosion, improving water quality, buffering against climate change, and providing essential habitat for a variety of wildlife. By stabilizing marshlands and preventing erosion, Spartina protects shorelines from storms, flooding, and rising sea levels, vital for coastal communities like South Jersey.

Spartina creates safer, cleaner environments and supports local economies through industries like fishing, tourism, and agriculture. Acting as a natural filter, Spartina traps excess nutrients and pollutants, keeping coastal waters clean.

As a natural carbon sink, it absorbs carbon dioxide from the air and stores it in the soil, helping to reduce greenhouse gases and combat climate change.

Most plants convert sunlight into energy and food through photosynthesis. In salt marshes, Spartina grasses perform photosynthesis to supply the soil with oxygen and essential nutrients, forming the foundation of the food chain. As a keystone species, Spartina supports biodiversity and helps stabilize the environment both structurally and ecologically.

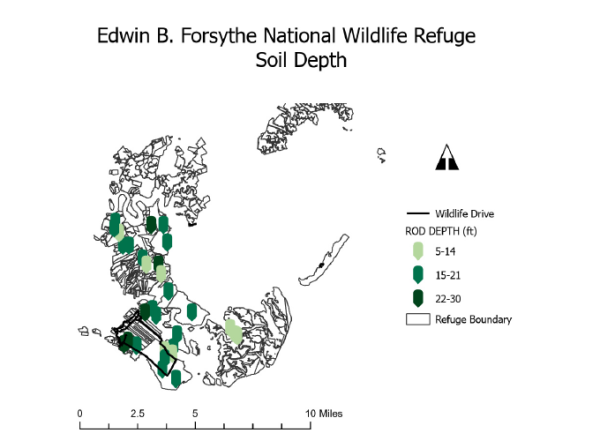

Spartina’s survival secret lies in its remarkable root system.

The plant’s roots go deep into the soil, and spread out and form thick patches that interlock and intertwine with the roots of nearby Spartina plants. This creates a dense, woven underground network, making the entire marsh surface more stable and resistant to washing away, and creating a haven for young marine life, shielding them as they develop.

Above ground, its grass-like blades play an essential role in trapping sediment.

The dense growth of the blades creates a natural barrier that slows down water movement, causing sediment carried by the water to settle around the plants. This grass provides shelter, food, and nesting grounds for many species, including migratory birds, small fish, and invertebrates.

However, rising sea levels, invasive species, and expanding coastal development are putting increasing stress on Spartina.

Protecting Spartina and preserving wetland ecosystems are essential steps in mitigating these devastating effects. As this vital and vertical grass disappears, so do the species that depend on it, contributing to the broader pattern of the Sixth Extinction.

Andrew Lewis, environmental journalist and South Jersey native, explains that wetlands are trapped in what’s known as a “coastal squeeze.”

“The problem is, human development has pushed up against these marshes, creating a ‘squeeze’ where the wetlands have no room to move inland as sea levels rise. These marshes once had room to expand, but now they’re trapped between developed land and rising waters.”

A wetland is like a sandwich, trapped between two slices of bread: on one side, human development with buildings and roads presses in, and on the other, rising sea levels driven by climate change push up.

This squeeze makes it difficult for Spartina to survive. Frequent storms and rising seas are eroding habitats and freshwater basins, drowning Spartina in some areas.

Adding to these pressures, invasive species like Phragmites, also known as common reed, are tall grasses that quickly spread and outcompete native plants like Spartina for space, nutrients, and sunlight.

Unlike Spartina, Phragmites have a much less effective root system for stabilizing marshlands, and they don’t have the same ability to trap sediment or filter water. The competition from Phragmites weakens Spartina’s growth and reduces its ability to filter water. As a result, coastal areas like South Jersey become more vulnerable to erosion and flooding.

Metthea Yepsen, Bureau Chief of the Division of Science and Research at the Bureau of Environmental Assessment for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, offers sustainable approaches,

“Solutions include rebuilding marshes with a natural slope as an effective strategy,” Yepsen said. “This allows waves to gently roll over the slope and dissipate, minimizing erosion. Also, using living shorelines, which are natural shoreline stabilization techniques that incorporate native vegetation and other natural materials to reduce erosion, protect coastal habitats, and improve ecosystem health.”

Yepsen’s insights highlight the importance of working with nature rather than against it. Rebuilding marshes with gradual slopes and incorporating native vegetation through living shorelines are practical, proven ways to strengthen wetlands without relying on hard infrastructure. These techniques not only protect the physical landscape but also support the rich biodiversity that wetlands sustain.

Environmentally integrated solutions, like living shorelines, offer hope, but as Yepsen emphasizes, “Wetlands require adaptive management and long-term, field-based monitoring to respond effectively to changing environmental conditions.”

Their success depends on careful planning, long-term monitoring, and a willingness to adapt as environmental conditions shift, reminding us that restoration is not a one-time fix, but an ongoing commitment.

Local residents can make a difference by supporting wetland restoration projects, avoiding harmful lawn chemicals that pollute waterways, attending town meetings on coastal development, and helping to protect the natural spaces in their backyards.

The concern is that the ongoing loss of Spartina will leave coastal communities more vulnerable to stronger storms, polluted waters, and the collapse of vital fisheries that many people depend on. But advocates say there is still hope, that residents and officials can protect Spartina, preserve the wetlands of South Jersey, and defend one of our strongest natural allies in the fight against climate collapse.

This isn’t just about saving a single plant species, they argue, but preserving the intricate web of life that depends on healthy marsh ecosystems before the Sixth Extinction claims another victim.

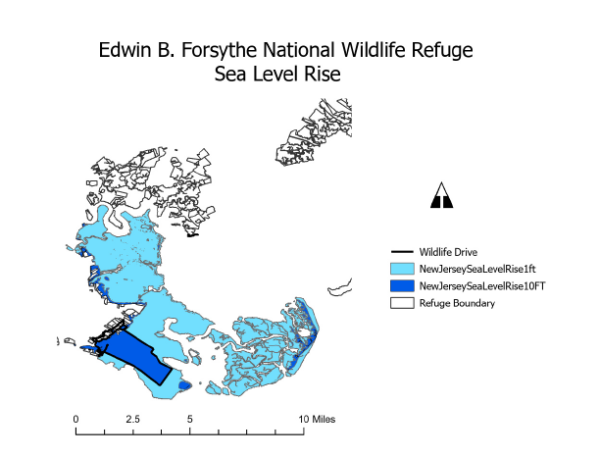

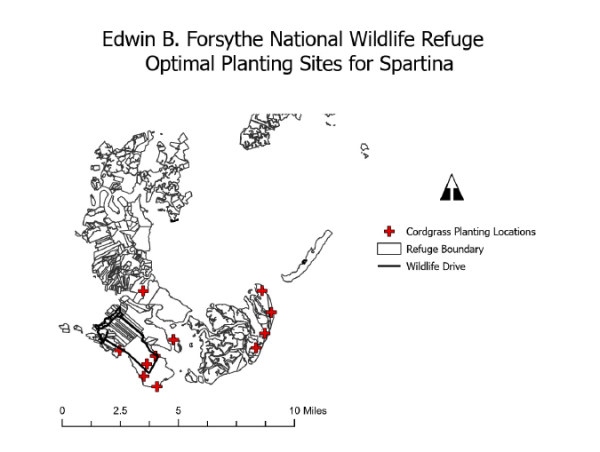

Note: The graphics in this article were produced by a student, Jayna Petrosh, mapping optimal Spartina planting sites in the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge in Atlantic and Ocean counties. Using data on sea level rise, wetland distribution, and root depth, the map identifies ideal zones for vegetation restoration to boost coastal stability and resilience.