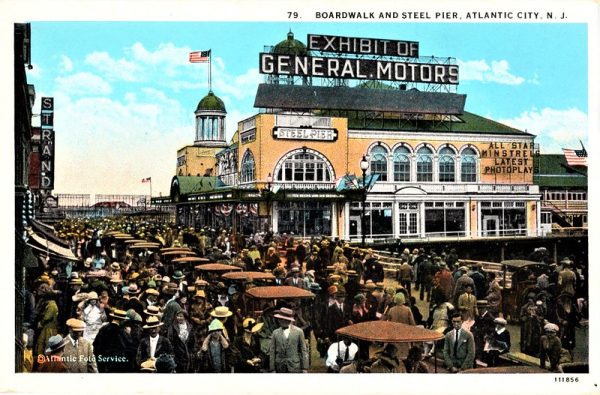

Atlantic City’s cultural identity in the last 50 years has been largely defined by its casinos and its status as a beach resort town. However, the city has an infrastructure problem.

Despite having assets like the Atlantic City Expressway, an airport, train and bus stations, and nine casinos with the capacity to host over 27 million visitors annually, the assets aimed at Atlantic City locals could possibly be washed away in the next decade.

A June 2024 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists identified Atlantic City as having some of the most at-risk infrastructure in the nation for flooding due to sea level rise and climate change. It notes that a 3.2-foot increase in sea level based on a moderate scenario for sea level rise would expose 44 public and affordable housing facilities to biannual flooding by 2030. Data from First Street, a climate risk organization, also ranks the city as facing severe-to-extreme flooding risks across its infrastructure.

The challenge of maintaining and preparing much of Atlantic City’s climate infrastructure comes from the city’s management of finances. This office’s effort will be hampered, however, by debt brought on by recent events.

“Atlantic City has no capital funds,” said James “Jim” Rutala, who serves as a grant consultant for the city’s climate mitigation projects. “It’s the only city in the state of New Jersey that does not have access to capital because of various financial issues that have happened in the city’s past.”

Atlantic City’s overreliance on the casino industry to bring in business has led to the lack of capital funds. Events in the past 20 years like the 2008 financial crisis, Hurricane Sandy, four casinos closing in 2017, and then the COVID-19 crisis led to a ripple effect that caused the city to take on over $500 million in debt in the last decade. Today, the physical casino industry is continuing to suffer after the rise of online gambling. Just this year, the remaining Atlantic City casinos faced a 14% decline in operating profits in the third financial quarter.

As a grant consultant, Rutala helps to facilitate priority climate resiliency projects for the city, such as replacing and maintaining bulkheads along the water in various neighborhoods and any other environmental sustainability or climate-related grants for which the municipality can apply.

Federal money is available

“The state government isn’t involved in infrastructure right now,” Rutala explained. “There’s not investing at all in infrastructure, they’re investing in regulation. [The U.S. Army Corps of] Engineers are investing in infrastructure. The Federal government as a result of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) has provided significant dollars for big projects. FEMA has continuously been a source of funding. The city applies for FEMA funding every year and gets it every year.”

In 2022, Rutala prepared a FEMA application and other funding requests that resulted in a $5.4 million grant that went toward flood protections for the city, most notably over $5 million of the grant went towards the construction of a pump station project on Atlantic Avenue.

According to Rutala, Atlantic City is far better equipped to deal with a climate crisis than some other coastal communities further south in New Jersey. Rutala says that places like Strathmere or Reed’s Beach further down the coast are more vulnerable to sea level rise by their small size and lack of economic output to the state.

“Even the federal government has to do a cost-benefit analysis when they invest millions of dollars in a project,” Rutala said. “If you’re protecting an industry that generates $8 billion a year in revenue and feeds all of South Jersey, the decision becomes easier than if it’s a commercial community that doesn’t provide that kind of economic engine.”

Atlantic City’s position as a multi-billion-dollar revenue stream for the state and local economy far outweighs the costs of resiliency projects like raising buildings or pumping in sand to replenish beaches.

Some of the most notable assistance comes from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The USACE is typically responsible for dredging sand onto the beaches that surround Atlantic City and Absecon Island. Lately, the USACE in collaboration with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) has been focused on a study of New Jersey’s Back Bay, where most of the city’s residential neighborhoods and public housing developments are located.

Focus on the Back Bay

In December 2024, the USACE released a draft report detailing some of the findings from the years-long study. Some of the report details include an updated plan of action which calls for the elevation of approximately 6,400 residential buildings and floodproofing over 200 critical infrastructure facilities like police stations and hospitals across the state’s Back Bay region, of which Atlantic City is a part. The plan has not yet been approved by authorities, including the U.S. Congress or funded for implementation at the state or federal level, and is thus subject to change.

If the USACE’s plan of lifting residential buildings were to come to fruition within Atlantic City’s housing market, it could face substantial difficulties compared to other municipalities in the state’s Back Bay. Atlantic City’s housing market is unique among others in the state, with 42.9% of rental units (11,282) in the city being federally subsidized through either housing choice vouchers, project-based section 8, or public housing. The city also has 4,925 total vacant housing units, which represent close to a quarter of the total available housing in the city. Owner-occupied housing drops even lower than the city’s vacant units at 4,223 units. This means that if a substantial amount of housing in the city were to be raised to meet flood resiliency standards, it runs the risk of displacing a considerable number of the city’s residents.

According to Councilman Jesse Kurtz, Hurricane Sandy, one of the worst storms in the recent era to hit the region, heavily contributed to Atlantic City’s housing issue.

Kurtz represents the 6th ward of Atlantic City, which encompasses much of the Chelsea Heights and Lower Chelsea neighborhoods. In Kurtz’s experience, most of the workforce housing in town was basement or first-floor apartments in old homes, which were targeted by the flooding during Sandy.

The resulting process of restoring the area after the storm caused owners who wanted government resiliency funding to either update or upgrade their homes to the new flood standards or instead build new construction on their lot. The resulting new construction has exacerbated the existing need for affordable housing because it cannot be offered at an affordable rate.

“It’s sent a lot of working people off the island to live, but then they still have to commute into town,” Kurtz said. “And so flooding has indirectly played a role in that. It’s kind of a self-feeding problem because then if more people need to commute to get into town, in times of flooding, more institutions and so on will not be able to function.”

The public and affordable housing market in Atlantic City has been under increased scrutiny in recent years as a result of a lack of funding for the city’s Housing Authority. Residents of Stanley Holmes, one of the oldest affordable housing villages in the state and country, have been suffering from a lack of heat, hot water, and other utility issues for the past several years.

In 2024, Representative Jeff Van Drew, whose district includes the city, launched a criminal complaint against the Atlantic City Housing Authority. In January, Van Drew released a statement after speaking with Scott Turner, the nominee for Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, detailing a visit to Atlantic City and potential federal intervention from Turner.

Private investment as an option

Because of the city’s unique financial position, it has largely had to turn to private investment to improve upon itself. This process has typically occurred on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis.

In the last four decades, private investment through community development corporations (CDCs) has begun to pop up in many of the city’s major neighborhoods, such as Chelsea, Ducktown, Midtown, and the Inlet. These CDCs are neighborhood-specific and formed by communities’ residents and outside investors looking to help revitalize the city.

“There are so many peaks and valleys in Atlantic City infrastructure,” says Evan Sanchez, co-founder of Authentic City Partners and one of the driving forces behind the Orange Loop neighborhood in the city. The Orange Loop is a three-block area along the city’s beach block stretching from New York to Tennessee avenues that has been largely redeveloped into a food and culture hub for the city.

Newer public and affordable housing needs to be built in tandem with fair market housing at the same time to ensure an equitable quality of life for residents. One of the most recent attempts at making the Atlantic City housing market more equitable was through a first time home-buyer lottery in the Venice Park neighborhood. This housing program would not have been possible without the aforementioned community development corporations’ investments.

“So it’s an interesting thing where you build infrastructure for max capacity and then you just don’t have max capacity very often,” Sanchez said. “I think that’s one of the things I think about in general as a business and real estate owner when you deal with the seasonality of Atlantic City seriously.

“I have long-term tenants that are there all the time and I think about infrastructure in terms of the housing stock and the very limited quality housing in the city of Atlantic City,” he added. “There needs to be much more of that over a long period of time so that you have people living here year-round.”

Correction: A caption in an earlier version of this article stated the building at 137 South New York Avenue was vacant. The site currently hosts Sciullo Engineering on its second floor and will house a bar on its first floor later this year.