Additional reporting by Olivia Armstrong

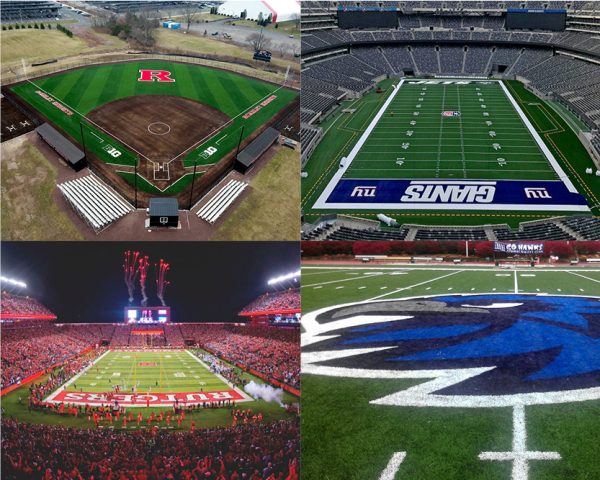

With the world’s attention turning to New Jersey in 2026 for the FIFA World Cup, one critical story won’t be about the athletes on the field — but the field itself. More specifically, from the playing surface at MetLife Stadium, where the final will be held.

The stadium, which has always had artificial turf, will switch to a grass field for the big match.

The turf at MetLife Stadium, home to the New York Giants and New York Jets, has earned a bad reputation over the years, with players and fans alike holding it responsible for season-ending injuries for some of the NFL’s biggest superstars, such as Aaron Rodgers, and Kyle Fuller.

Still despite installing a new grass field for the World Cup, the New York Giants owner said they are sticking with turf for the upcoming NFL season.

MetLife isn’t the only turf field generating controversy. And it isn’t just about professional athletes.

New Jersey is home to hundreds of turf fields that are used for little league, high school, and college athletics, but also at parks, playgrounds, daycares and even residential homes.

In addition to concerns about sports injuries, turf fields present a range of environmental issues.

Across the state, municipalities and schools are weighing the pros and cons of grass versus turf fields, with little federal guidance. As a result there is a lot of confusion and a lot of heated debate.

The environmental pros and cons of turf and grass

The primary benefits of artificial turf is that it’s easier to maintain and is durable.

Turf fields don’t need to be watered, mowed or re-seeded. They are pest free. Athletes can play on them in wet conditions without damaging the field. And decision makers often like knowing the up-front costs.

“Synthetic turf is great just from a maintenance aspect,” says Tim Bast, owner of ForeverLawn of South Jersey, a company that installs turf. “There’s an environmental impact with synthetic turf, but it’s usually upfront and one-time, and, residentially, the turf can last 20 years-plus.”

The downside of turf is that it is made of chemicals and materials that can come in contact with skin and clothing and wash into ground and water systems.

Turf also traps heat – which makes it hotter for athletes and can lead to dehydration and even burns – and raises the temperature of an already warming planet. A study by the Penn State Center for Sports Surface Research found that turf can be as much as 50 degrees hotter than grass.

But grass fields have environmental impacts as well.

Grass requires a lot of water, which is a problem in areas with summer water restrictions. They have to be maintained with lawn mowers, which burn fossil fuel and emit pollution. Fertilizer and herbicides can also leak into wetlands and marine ecosystems through stormwater runoff, causing destructive algal blooms.

On the flip side, grass fields are cooler, trap carbon dioxide, absorb excess water, and help prevent soil erosion. And digging up grass to install plastic just isn’t natural.

“In my opinion, working with Mother Nature by implementing proper soil care and grass is optimal,” said Kathy Glassey, Senior Consultant for Inspire Green, Inc, a company that provides lawn care consulting. “When we ensure the soil ecosystem is well balanced, we are ensuring our planet is left in a better way than when we found it.”

Veterans Stadium: A history of turf health concerns

Turf fields come with the risk of spreading the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) chemicals to anyone who uses them. These substances, also known as “forever chemicals” due to their ability to stay in the environment for long periods of time, come with some serious health impacts.

Some of these include, but aren’t limited to, an increased risk of certain cancers, reproductive problems, suppressed immune systems, increased cholesterol levels, and cardiovascular system impacts.

The EPA recently issued rules on PFAS, stating that companies are required to immediately report releases of PFOA and PFOS that meet or exceed one pound within a 24-hour period to the National Response Center, and also to state tribal and local emergency responders. The agency deemed it essential to quickly catch PFAS contamination because “any delay allows the chemicals to migrate into the soil and water supplies. However, the rule could also compel companies to clean up contamination that had occurred years before if it’s detected in the new compulsory tests,” The New York Times reported.

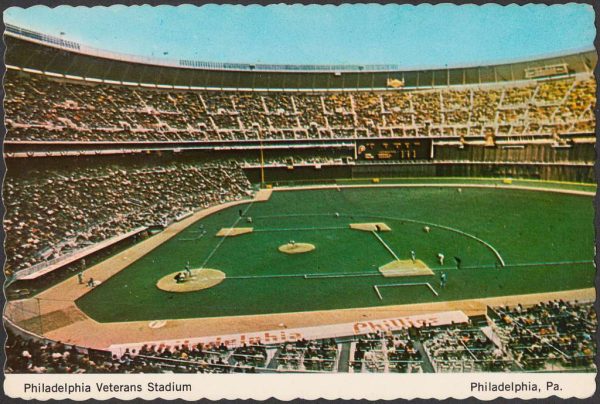

Veterans Stadium, the home of the Philadelphia Phillies and Philadelphia Eagles from 1971 to 2003, made headlines due to these “forever chemicals.”

Six former Phillies players — Darren Daulton, Ken Brett, David West, Johnny Oates, Tug McGraw, and John Vukovich — all died of a fast-growing and aggressive brain tumor called glioblastoma before the age of 60. Studies have found that the brain cancer rate in the 532 players who played for the Phillies during the Vet’s lifespan is around triple the average rate of adult men.

“You can’t help but think about it,” Larry Andersen, a pitcher for the Phillies in 1983-86 and 1993-94 told the New York Times. “It would be nice if there were some answers, if nothing else going forward. But nobody knows anything. It’s frustrating.”

Despite the connections that have been made between artificial turf and glioblastoma, the cause of the disease is still widely unknown.

What do athletes prefer?

Despite the potential health risks, plenty of athletes still prefer turf over grass.

Rowan University, located in Glassboro, features both for its Division III sports teams. The main football stadium, soccer and lacrosse complex, and practice fields are made of turf; the baseball and softball fields have grass.

Chris Popper, 33, a former Rowan University football player, preferred to play on turf for one reason.

“The one benefit I believe turf has over grass is speed,” said Popper. “Essentially, players are slower on grass than turf.”

Tyler Cannon, a senior second baseman for Rowan’s baseball team said field conditions are also key.

Rowan’s baseball field has problems with flooding, as the right side of the field line doesn’t drain well, leaving puddles and ultimately causing canceled practices.

“You know what you’re getting [with turf],” said Cannon. “It’s consistent, and it allows for more margin of error for practice, because it’s not getting affected that much from the rain. Being a Northeast baseball team, it’s super important to get outside in those cold weather months.”

But many players also fear turf because of the risk of injuries, especially as players reach the higher-levels of their sport.

In 2020, the U.S. Women’s National Soccer team won a long-running battle to play on grass rather than turf, citing poor turf conditions and injuries.

In 2022, NFL players called for a ban on turf fields altogether after Odell Beckham Jr. went down in a non-contact incident during Super Bowl LVI. Beckham’s injury, along with others that didn’t involve contact, are due to the fact that turf fields don’t have as much “give” compared to grass fields, leading to players’ cleats getting caught or jammed.

New Jersey locals battle it out

The debate about turf versus grass is playing out at the local level across New Jersey.

Two years ago, the town of Ocean City had a spirited debate about the future of its athletic fields on Tennessee Avenue.

On one side of the argument were high school coaches, athletes and parents, who wanted artificial turf, arguing that it was more durable, low maintenance, and could be used year-round in wet weather. On the other side were environmentalists and residents concerned about microplastics washing into surrounding wetlands and ocean.

In the end, Ocean City’s council voted 6-0 for turf. “It just seems overwhelming the number of people who want this,” Councilmember Jody Levchuk told OCNJ Daily.

A similar debate in Princeton ended with a different result. The town put a hold on a project to install a turf field at Hilltop Park after the town’s Environmental Commission argued against it based on environmental and financial concerns.

Similar debates have played out in the towns of Maplewood, Westfield, Belmar, and East and West Orange and will be repeated in other locations in the future.

Frank McGehee, the former mayor of Maplewood, told New Jersey Monthly that the grass versus turf debate in his town was “one of the most divisive issues that I’ve ever experienced.”

“With everything happening in the last couple years, from the pandemic to the Black Lives Matter movement, it’s ironic that this issue became the issue,” said McGehee.