In Egg Harbor Township, about a 20-minute drive from Atlantic City, a flock of 18 chickens peck away at food scraps. Their owner, Chef Salvatore “Sal” Giambrone, 42, gives them a combination of his family’s food waste and leftovers from his new Ventnor restaurant, The Queen Bean Bistro.

Giambrone runs a tight ship. In the first few months of the restaurant’s operation, he has been able to refine his food waste down to a science, which is unusual in the industry.

“A lot of kitchens, I’m not going to lie, I’ve been doing this 26 years, it goes right into the trash,” said Giambrone.

Giambrone’s chickens – in addition to providing fresh eggs – are also doing a small part to help New Jersey reach a massive sustainability goal: to cut the Garden State’s food waste in half.

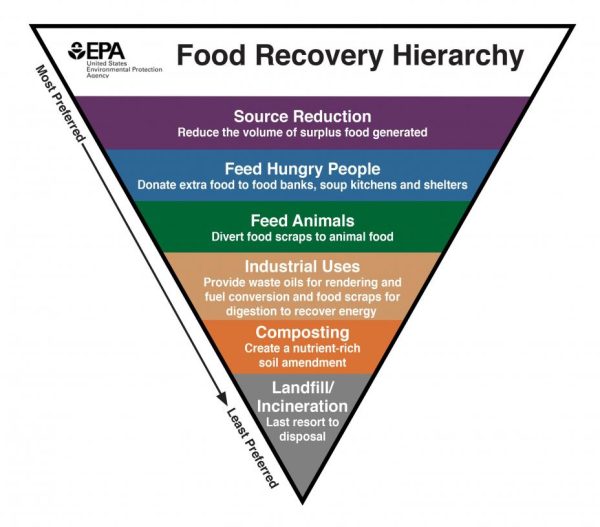

To reach that goal will take a variety of approaches, including converting food to renewable energy, regional and local composting initiatives, using it for livestock feed, and providing incentives for businesses and individuals to do more than throw food away.

A Look at Global and Garden State Food Waste

A third of all food grown and produced for consumption is never eaten.

This is food that could be used to help feed those without enough to eat. Globally, 45% of all people experience food insecurity.

This is also a waste of water, land, labor and money. It costs industrialized countries an estimated $680 billion a year.

Food waste is also the largest contributor to solid waste at a local level. It takes up valuable landfill space and releases methane which contributes to global warming. Most of New Jersey’s landfills are currently at or near capacity.

In an effort to remedy this, New Jersey enacted the Food Waste Reduction Act in 2017 with the goal of reducing the state’s annual food waste by 50% by 2030.

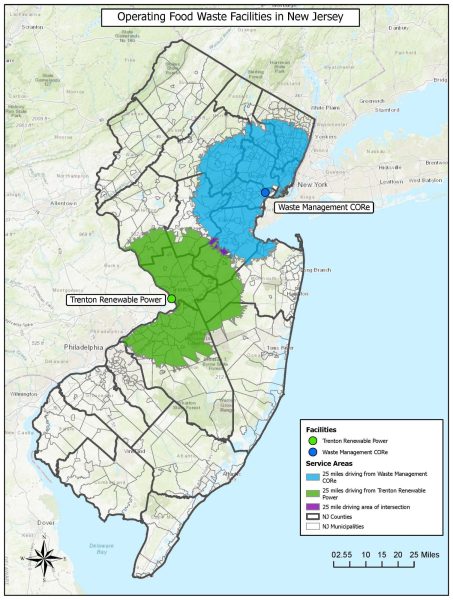

One of the key strategies for doing this is by creating renewable energy from the wasted food through methane capture or by burning it. There are currently two facilities that are authorized to recycle food waste, one in Trenton and the other in Elizabeth.

Governor Philip Murphy made sustainability pledges last year to convert all of the state’s energy to renewable sources by 2035, largely through offshore wind and solar.

Food waste is noticeably absent from the governor’s top priorities, and the financial incentives that some renewable industries receive do not currently exist for food waste industries.

In January 2024, State Assemblyman Robert Karabinchak introduced Act 1475 for the upcoming legislative season. It’s an amendment to the state’s already existing food waste recycling legislature requiring large food waste generators to send their waste to a recycling plant within 25 miles of their location.

While this approach shows promise in the more densely populated northern part of the state, it is more challenging in southern New Jersey.

Currently only 33 municipalities of the 252 served by the food waste facilities are located in South Jersey.

The state’s Department of Environmental Protection acknowledges the need for additional facilities in the southern part of the state. But building new ones is costly.

“It is often less expensive to just dump the stuff than it is to actually handle it and reuse it and recycle it in some way,” said Dr. Garrett Broad, an associate professor at Rowan University, who studies food sustainability. “And so that’s kind of the big challenge that we’ve been facing, that the sort of economic incentives historically have not been there within institutions to invest in a real strategy for food waste.”

At the Store and in the Kitchen

Individuals can start by refining their meal planning and grocery lists. The majority of food waste is ready-to-eat food that never gets eaten. People can cook in smaller quantities so they are less likely to throw away uneaten food. Only buying food that will be used prevents spoilage.

Restaurants and food commercial handlers, which can have some of the biggest impact, also need to change the way they operate.

At the Queen Bean, for example, Giambrone takes every effort he can to incorporate scraps back into dishes on the menu to increase the amount of yield on his produce. For example, people will typically discard about 10% of a tomato. While insignificant on its own, it does contribute to the 3.5 pounds of food waste each person makes each week.

“I do slice tomatoes for sandwiches, obviously the tops and bottoms that’s ‘trash,’ if I take that and chop it up now I have bruschetta and I put that on something else on the menu, now I have cross utilization,” said Giambrone. “The only thing I have left is that stem now that centerpiece, I’ve had 98% utilization from this, like that’s great in my mind.”

Learning to Compost

Until more food waste to energy infrastructure can be built in South Jersey, the problem will have to be tackled largely on the local – and even backyard – level.

Composting is another way to divert their kitchen waste into their gardens and flowerbeds.

Home composting kits can be purchased at most garden centers and big box stores. Some local governments offer discounts or incentives. Residents of Gloucester County, for example, can purchase an Earth Machine home composting kit at a discounted price.

While composting is a great solution and practice, it has some barriers to entry.

The home-composting kits that several municipalities offer at a discounted rate are a great way to combat food waste. However, without any active social or educational campaigns enacted with the purpose of making sure compost is done right, the practice itself may be rendered futile.

“I think this is the big challenge with home composting is oftentimes folks don’t really follow the rules of what should be put in those home composting bins,” said Broad. “Otherwise you lead to a lot of contamination, and then people have put a lot of this effort into this process, but it still ends up where it would have gone in the first place without this, which is the landfill, right?”

For those that don’t have space for backyard composters, municipal or private composting services can be an option.

To learn more about food reducing opportunities in your area, here is a county-by-county summary of local efforts:

Atlantic County

To help keep food waste out of the landfill, the Atlantic County Utilities Authority (ACUA) offers composting classes and resources. In addition, its food recycling page lists a variety of local pig farms that will dispose of food waste and the contact information for Ag Choice Organics Recycling, a private company located in Sussex county that converts food waste into compost and animal feed.

Cape May County

Cape May County has provided a two-pronged approach to the food waste issue surrounding its people. The Cape May County Municipal Utilities Authority (CMCMUA) encourages its residents to compost their own food waste at home to combat the lack of food waste recycling its county can offer. The CMCMUA takes advantage of the food and other organic waste that ends up in its landfills by using a methane capture system which it’s been employing since 1984. The landfill gasses captured provide renewable energy in the same fashion as the facilities in Trenton and Elizabeth.

Salem County

Similar to Cape May, the Salem County Improvement Authority recommends that people compost their food scraps in their own gardens.

Cumberland County

Cumberland County does not currently list any food waste specific recycling programs across its utilities authority website. In 2023, received $500,000 in grants as a result of being one of the leaders in the state’s recycling efforts. This is thanks to the Recycling Enhancement Act,which distributes funding in accordance with an area’s recycling efforts. The funds must be used to improve recycling initiatives including composting, which will in time help to reduce the area’s food waste.

Gloucester County

Gloucester County focuses its food waste recycling efforts on the individual level. Allowing residents to purchase a limited quantity of Earth Machine Home Composter kits at a discount. To date 2,385 kits have been sold to county residents with an estimated 1.4 million pounds of food waste diverted from regular waste disposal streams on a yearly basis. Rowan University, the county’s third largest employer, used to have a dedicated chapter with the Food Recovery Network and the robins nest group home. After the Robins Nest was sold to Acenda Integrated Health, the chapter became inactive.

Camden County

Residents of several Camden County towns can opt to subscribe to a pick up plan with Garden State Composting. A composting company started by Ian Urqhuat and Catie Doherty. The county also initiated a pilot program in 2020 that sought out vendors county wide to pick up and dispose of food waste.

Burlington County

While some large Burlington County food waste generators can send their food waste to the Trenton waste facility if they are close enough, the county still encourages individuals to compost their own lawn and food waste.