Is New Jersey just a dumping ground for New York City’s and Philadelphia’s garbage?

Does the mob really run trash collection like they do in The Sopranos?

Does your plastic water bottle ever get recycled?

Dr. Jordan P. Howell, an associate professor of sustainable business at Rowan University, explores these questions and more in his new book Garbage in the Garden State. The book unpacks the history of waste management in New Jersey and topics like landfills, recycling, politics and organized crime. And he finds that New Jersey has a lot to teach the rest of the U.S. about how to handle – or how not to handle – the things we throw away.

We sat down with Dr. Howell to learn more. In this Q&A, he talks about his book’s inception, what he learned, and dispels some of the myths and misconceptions about garbage and recycling. The following is an edited transcript of a conversation.

Interview by Chloe Cramutola

Q: What inspired you to write a book about New Jersey’s waste history?

Dr. Jordan Howell: I’ve been researching waste and recycling industries for about 10 years, and I’ve been at Rowan University learning about the history of waste in New Jersey. It seemed like an interesting and important story to tell.

As I was working on it, it became clear that New Jersey has played a really important role nationally, as far as how other places deal with waste and recycling, and I felt like there was not a lot of awareness of that.

New Jersey is often the butt of a lot of jokes about garbage – and there’s some element of truth to that – but it’s worth understanding why those stereotypes exist in the first place.

Q: At the beginning of your book you use examples from TV shows like The Sopranos and Futurama that stereotype New Jersey as a “wasteland.” However, you argue that the state helped pioneer waste management in the United States. Can you briefly explain?

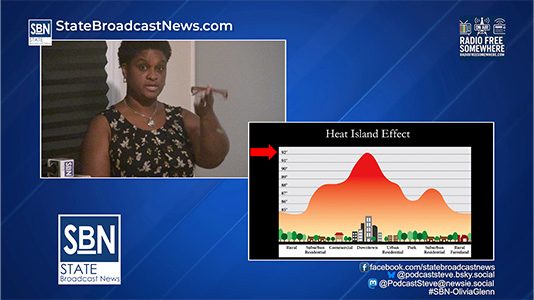

Dr. Howell: New Jersey had to figure out pretty quickly how to deal with a lot of waste. Being sandwiched between New York City and Philadelphia, both of those cities saw New Jersey as a natural place to send their garbage because it wasn’t as densely populated, and there was land available. We also have a lot of industrial activity and military activity, so we had to figure out, “What are we going to do with all this stuff?” Initially, it wasn’t very good.

People don’t want to have garbage dumps everywhere, so we had to develop an organized approach to deal with waste management. It wasn’t so much about how to build a great landfill, or how to incinerate, or how to recycle – that technical stuff isn’t necessarily what New Jersey’s contribution has been. It’s been more about planning from a waste management perspective and also a legal perspective. New Jersey was one of the first states to require counties and cities to have waste management plans.

You highlight the importance of our perception of waste. How do you define waste?

Dr. Howell: New Jersey has a legal definition of waste and recycling. And for some people that seems unnecessary…“Why is the government trying to define waste?” But if you’re trying to plan for waste management, you have to have a definition of what is waste and what is not waste and therefore, there are certain things that are subject to the rules and other things that are not. Also that’s really important when it comes to recycling, defining what can you recycle, what can’t you recycle.

The perception of whether something is useful or not is important. One of the things that’s interesting about waste and recycling is that most people have their own understanding of whether something should be thrown away or put in a trash bag. And some of it depends on how you were brought up or where you live.

If you live in a rural area, and you really like gardening, then your food waste might not really be waste because you can compost it. Or if you live in a town and don’t have anywhere to compost, then food waste goes in the trash. It’s the same material, but two different perspectives on whether or not it’s waste.

So there is some amount of perception, but there’s also some amount of education, in defining what is waste and recycling.

Q: It seems there is a lot of confusion around recycling. Are there insights from your research or life that would be helpful to the average person?

Dr. Howell: I’m probably much closer to the system than the average person. For me, the key determinant is that I try to understand what types of things are actually recyclable in my town. They publish a list of what they collected and what they don’t. Just paying a little bit of attention to the types of plastic that they want, the types of paper, metal, and glass. And realizing that you’re going to have to throw out into the trash some stuff that maybe if you lived elsewhere would be put in the recycling bin.

So just trying to be conscious of what is actually recyclable in my town, or where I work, is the first step. If we make it harder for the towns and the recycling facilities to actually sort the stuff that has economic value, then they end up losing money, and it becomes a losing proposition to do recycling.

Trying to pay attention to what actually is recyclable is really important.

Q: That leads me to my next question. You also discuss the recycling versus incineration debate from the 1970s and 1980s. How has that shaped things today?

Dr. Howell: I think the biggest thing I would want people to understand about recycling is that – from a planning perspective and from a political perspective – it is not really about conserving resources. Recycling is about keeping things out of a landfill or out of an incinerator.

It’s really hard to open a new landfill. It’s potentially even harder to open a new incinerator.

Trying to manage the lifespans of landfills and incinerators has been a real concern among policymakers for the last 50 years. We really want to extend the life of stuff that we have now, because it’s so hard to make new ones. In New Jersey in particular, we’re very small, very densely populated, so there’s almost a zero percent chance of a new landfill.

The question becomes: “What can we do to extend the life of the ones that we have?” One way is to pull as much out of the trash stream and call it recycling.

In theory, there is an economic value to recycling. For example, you can sell the material and someone will use it and put it in their products. But it’s really hard to make a lot of money in recycling. Some private businesses have been successful, but it’s pretty hard to become really successful for a long time.

The other thing that I would say about recycling is that we seem to be focused on consumer products. We want the plastic bottle that goes in the recycling bin to come back to life as another plastic bottle in this beautiful closed loop. That’s not really realistic.

A lot of times in the recycling process, the material gets downgraded into lower quality material. That doesn’t mean it’s worthless, but it often has to be made into something different. A lot of carpet, for instance, can be made from recycled plastic. But a lot of folks don’t necessarily understand that kind of cycle.

Q: So what are the benefits of recycling – economic and otherwise?

Dr. Howell: Recycling is a complicated market. In recycling, we hope to sell recycled material to someone who wants to use it. But there are a lot of extra costs associated with processing the material. You have to sort it. You have to get it to a uniform consistency that can be used by a manufacturer. Often the cost of the processing is higher than what it is worth.

When prices are really low for recycling material, or there’s a lot of volatility around prices for recycled material, it sends negative signals to the folks that are actually doing the recycling work. Also it sends negative signals to companies or towns that are collecting recycling because it’s not profitable. And then recycled material can end up in a landfill.

Also each material has its own unique market dynamics. Recycled paper, for example, has really different market dynamics than recycled plastic or glass. And it’s regional. So the East Coast markets look different from the Midwest or the South East or the Pacific Northwest. And then internationally, it looks really different.

That said, recycling is also a way of getting people to have a greater awareness about environmental issues in their everyday life. That’s extremely valuable.

Recycling is taught to little kids in school in New Jersey, and it is required to be part of the K-12 curriculum. Kids are learning about it.

Whether or not recycling as a process ultimately matters, the exposure to environmental issues and thinking about our impact on the planet may be the most valuable aspect.

Q: At the end of your book, you state that waste is not a problem that can ever fully be solved. So what do you think this means for the future of waste management in the United States? Where do you see it going in the future?

Dr. Howell: One thing that bothers me about some of the environmental perspectives on waste is the promotion of the idea of “zero waste.” Zero waste has to be a myth, by definition, because there’s always going to be things that we can no longer have value.

You have to recognize the fact that there’s always going to be some fraction of the waste stream that is going to have to be disposed of in a landfill or an incinerator. No matter how good a job you do with recycling and composting and all that. There’s just going to be some stuff that has to be thrown away. We can look back through all of human history and find that that’s true.

The reason we know about our ancestors from 20,000 years ago is through their trash.

If you’re operating with this goal of zero waste, you’re never going to get there. Eventually from a leadership perspective, people are going to get frustrated and not want to participate in that goal and say, “This is impossible, why are we working on this?” So while the zero waste rhetoric has the potential to inspire people to do better, it also has the potential to be really discouraging.

Certainly we can minimize waste. Some of our waste is a result of a ridiculous amount of packaging for certain products. It’s unnecessary. Some of those decisions about packaging are tied to things like mitigating the risk of lawsuits and contamination.

I think what’s interesting and surprising about learning about garbage is that some of our waste problems are not just about landfills and incinerators, but really our attitudes toward other things like consumption and consumerism. We see the symptoms of those things through the waste stream.

The waste is not necessarily the problem that we need to solve. Maybe there’s an underlying condition that we have to address somehow.

Q: For my final question, how has your perspective changed? Or what is one thing that surprised you after writing this book?

Dr. Howell: I think the biggest surprise for me in writing the book is that we have no idea what to do with plastic. Even in the year 2023.

There’s so much volume, low quality plastic, from a waste management perspective. It sits in a landfill, and it doesn’t break down. The market for most recycled plastic is really terrible. Prices are low. It makes more sense economically to dispose of plastic than to recycle it most of the time. That’s disappointing to me as a person who cares about the environment.

When plastics first emerged in the late 1970s early 1980s, people didn’t know what to do with it then either. It is this problem that no one has had a solution to, even though we’ve been talking about it for over 40 years. And that was sort of surprising. What have we been doing for 40 years, where the markets haven’t been developed? Or why have we stuck our heads in the sand about the fact that markets don’t exist? Why do we keep telling people, “Recycle plastic, recycle plastic,” but it really doesn’t do a whole lot environmentally?

I was really surprised at the depth and the extent to which we have created this enormous problem, but made no progress on finding a solution.