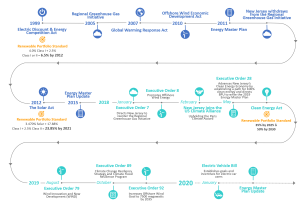

In recent years, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy has rolled out a series of green-initiative plans aimed at combating New Jersey’s biggest challenge – climate change. Sea level rise, increased precipitation, extreme weather phenomena, and rising temperatures are just a few of the many consequences of climate change outlined in the 2021 New Jersey “Climate Change Resilience Strategy.”

These concerns are addressed in the “Energy Master Plan” which was released in 2019. This plan includes six main priority areas within the field of green energy.

The first strategy, “Reduce Energy Consumption and Emissions from the Transportation Sector,” focuses on reducing the miles traveled by public transportation and switching out their gas-powered vehicles for more sustainable electric-powered buses.

Strategies two, three and five, to “accelerate deployment of renewable energy and distributed energy resources,” “maximize energy efficiency and conservation and reduce peak demand,” and “decarbonize and modernize New Jersey’s energy system,” focus on reducing our dependence on fossil fuels and transitioning into more sustainable clean energy alternatives.

“Reduce energy consumption and emissions from the building sector,” strategy four, does the same work as two, three and five but places a greater emphasis on the building industry. The plan states that “the building sector accounts for a combined 62% of the state’s total end-use energy consumption.” If an industry as large as this can make a substantial change in their fossil fuel consumption, then we could see a substantial change in New Jersey’s climate change contributions.

Lastly, strategy six, “support community energy planning and action with an emphasis on encouraging and supporting participation by low- and moderate-income and environmental justice communities,” focuses on bridging the gap when it comes to the disproportionate ways that climate change affects those of different socioeconomic statuses, both in education and living conditions.

All of these strategies come together to place New Jersey on track to complete Murphy’s goal of running New Jersey’s building and transportation sectors by “100% clean energy by 2050.”

Signs of these plans coming into effect are evident through the various green energy initiatives, studies and grants to endorse green jobs throughout South Jersey.

Solar Energy

Whether you’re sending a text to a friend, baking a cake or walking at night by the light of the streetlights, chances are you’re using electricity. Electricity, however, isn’t always from a spark as many believe. Many times this electricity comes from the burning of fossil fuels.

These fossil fuels are a non-renewable resource, meaning once they are all used up they are gone, at least for a very long time. One article from the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and Biosphere based at Stanford University suggests that we will be out of oil by 2050, gas by 2060 and coal by 2090. It seems the new generation will be the one tasked with getting rid of fossil fuels and implementing alternative energy solutions.

In New Jersey, lawmakers are already taking steps to move the state away from a dependence on fossil fuels and placing a strong emphasis on renewable energy such as solar and wind energy.

According to New Jersey’s Office of Clean Energy (NJOCE), “as of February 2022 over 152,916 New Jersey homes and businesses have installed a solar electric system.” This is a result of New Jersey’s numerous programs aimed at incentivising residents to obtain most or all of their energy needs through solar power.

At first the program was named the “Legacy SREC Registration Program,” which allowed residents to register their solar systems with the state and receive credits for the surplus electricity they produced. These credits were, and continue to be, called Solar Renewable Energy Credits, or SRECS. A solar system would earn one SREC for every 1,000 kWh produced. These credits could then be sold for money.

That program was disbanded on April 30, 2020 and was, in turn, replaced with the “Transition Incentive (TI) Program.” The TI Program was created as a bridge between the previous “Legacy SREC Registration Program” and the new, currently in use, “Successor Solar Incentive (SuSI) Program.”

This program allowed residents to earn TRECs, or Transition Renewable Energy Credits. These credits could be sold to the TREC Administrator for an amount determined by the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. When the TI Program officially stopped taking new applications on Aug. 27, 2021, it was replaced with the SuSI program.

This program worked a bit differently than previous programs and included two sub-programs. One was aimed at residents, while the other was targeted towards businesses and energy providers. Participants of this program are eligible to earn SREC-II credits, while those who fell under older iterations of the program can still earn their respective TRECs and SRECs.

Unlike previous programs, however, the value of the SREC-II is not based on a single assigned value. SREC-IIs earned under the residential program, aptly named the Administratively Determined Incentive (ADI) Program, will be assigned a value based on administrative decisions. The non-residential program, the Competitive Solar Incentive (CSI) Program, will assign values to SREC-IIs via a “competitive process.”

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, about 2.8% of the country’s energy comes from solar power. This might not be the victory environmentalists were hoping for, however.

While it is true that solar panels are more a sustainable choice compared to fossil fuels, they also possess their own drawbacks. The chemicals used to create photovoltaic (PV) cells, which are vital to the function of a solar power plant, can have harmful effects on the environment around them. Leaking systems or run-off from the panels can also result in these chemicals leaching into the ground.

In addition, solar fields may result in the deforestation of a local ecosystem, leaving those plants and animals without a natural habitat. Furthermore, the light reflected back from a panel can cause the death of insects and even birds who are flying overhead.

Off-Shore Wind Energy

On Dec. 6, 2021, Rowan University in Glassboro announced a university-wide Catalyst for Sustainability Cohort. The goal of this project was to unite students and faculty across all disciplines and colleges against the effects of climate change.

“This is an exciting opportunity for innovative and entrepreneurial scholars who want to make impactful change—they will be the groundbreakers,” said Rowan University Provost Anthony M. Lowman in a press release. “We are driving our research by appointing a catalyst in every college and school on our main campus to position Rowan as a thought leader in sustainability research, education and policy.”

On March 21, Rowan announced they had received a $500,000 federal grant presented by the U.S. Congressman Donald Norcross. The grant money is intended to bolster programs meant to prepare students for wind-based energy jobs.

“We’re going to use the [‘2+2’ engineering technology degree programs] for mechanical engineers, electrical engineers and civil engineers, so that anybody who wants to get some foundational knowledge in wind power can do that,” said Dean Giuseppe Palmese in a press release.

This announcement comes after the reveal of Murphy’s Offshore Wind Strategic Plan, which aims to achieve 7,500 megawatts, or 7,500,000 kWh, of offshore wind energy by 2035.

“Expanding New Jersey’s offshore wind industry not only protects our environment but also creates good jobs and new opportunities for businesses,” said N.J. Economic Development Authority CEO Tim Sullivan in a press release. “Development of the Offshore Wind Strategic Plan is a critical step toward maximizing the environmental and economic potential of this brand new industry.”

Many South Jerseyans may be familiar with the Jersey Atlantic Wind Farm in Atlantic County. The state’s first wind farm and the country’s first coastal wind farm “produces approximately 19 million kWh of emission-free electricity per year, which is enough emission-free energy to power over 2,000 homes,” according to NJOCE.

This wind farm consists of five 380-foot wind turbines managed by the Atlantic City Utilities Authority. Their website states that “the wind farm has saved ACUA more than $6.5 million in energy costs and has prevented more than 66,200 metric tons of CO2 from entering the atmosphere since its opening.”

Despite the success of this on-land wind farm, the state government seems more interested in off-shore wind. This can have two basic explanations. The first is that the wind turbines are rather large and can be seen, in some cases, miles away. This may not be ideal for homeowners who want to look out their back window and enjoy the beauty of New Jersey.

The second explanation is much more practical. The wind speeds on the open water tend to be much faster than the breezes on land. This is due to the fact that the wind has a large open space to build momentum and nothing to prevent it from sailing through the sky. For those same reasons, off-shore wind also has the benefit of being more consistent.

“Offshore wind holds the tremendous promise for our future in terms of climate change, economic growth, strengthening our workforce, and job creation,” Murphy said in a press release. “New Jersey is already committed to creating nearly one-quarter of the nation’s offshore wind-generation market…climate action can drive investments in infrastructure and manufacturing, while creating good-paying, union jobs.”

These systems seem superior to solar energy, as they take up less space and do not require as many chemicals. However, there still are some drawbacks. The first is that these wind farms are costly to create and may require regular maintenance. While a solar company can come in and place solar panels on a house within a week and forget about it from then on, these wind farms require months of planning, construction and maintenance work.

In addition, while the effects of these wind farms on marine life is not fully understood, we know the noise these systems create can cause many natural species to leave the area. This can cause them to enter into new environments with different predators or a lack of their basic needs.

Furthermore, working on these farms requires workers to use a boat. This boat utilizes its own set of fossil fuels and has its own disturbances to the environment.

Altogether, “The Energy Master Plan,” “The Climate Resilience Strategy,” and the “Offshore Wind Strategic Plan” work to lower New Jersey’s use of fossil fuels, which is the ultimate goal of these climate programs.