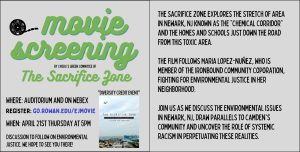

Rowan University hosted a screening of the documentary, “The Sacrifice Zone” about environmental degradation in Newark, followed by an open discussion about environmental justice issues in both Camden and Newark.

The screening was held both online and in-person on April 21 at Cooper Medical School of Rowan University auditorium. The event was sponsored by the CMSRU Green Committee and the CMSRU Office for Diversity & Community Affairs at Rowan University.

Filmmaker Julie Winokur, who directed and produced “The Sacrifice Zone” and who lives in Montclair, focused the film on the Ironbound section of Newark, which is experiencing a high degree of environmental pollution that is affecting the well-being of its residents. Winokur said in an interview with Gothamist that part of the film’s purpose is to inform N.J. residents how they contribute to the pollution problem.

“This is our trash. Our sewage, all the goods we buy that come through the Port of Newark and leave there on a diesel spewing truck,” she told the news organization. “This is our mess.”

The Climate Reality Project describes sacrifice zones as places “where residents – usually low-income families and people of color – live in proximity to polluting industries or military bases that expose them to all kinds of dangerous chemicals and other environmental threats.”

“It’s the willingness on the part of people who seek personal enrichment to destroy other human beings… And because the mechanisms of governance can no longer control them, there is nothing now within the formal mechanisms of power to stop them from creating essentially a corporate oligarchic state,” said journalist and current New Jersey resident Chris Hodges in an interview with Bill Moyers on Truthout.com.

The novel, “Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States” by Steve Lerner, details sacrifice zones as a major issue in the country since the 1970s, with their origins rooted in the long-term effects of strip-mining coal in the American West. Cities including those in the Louisiana and Texas petrochemical corridor, often referred to as “Cancer Valley,” can be considered part of a sacrifice zone. So too can the cities of Camden and Newark.

Camden

Camden was once a manufacturing powerhouse in northeastern United States. Once an East Coast center for creating some of the nation’s largest, incredible warships, Camden has become overshadowed with poverty, crime, and homelessness. With the second highest crime rates in the country, 40% of its nearly 70,400 residents are jobless and the population has had a near 40% decrease since the 1950s when its population totaled 120,000. The median household income and the median house value are significantly below those of the rest of the state, according to city-data.com.

licensed under CC BY 2.0.

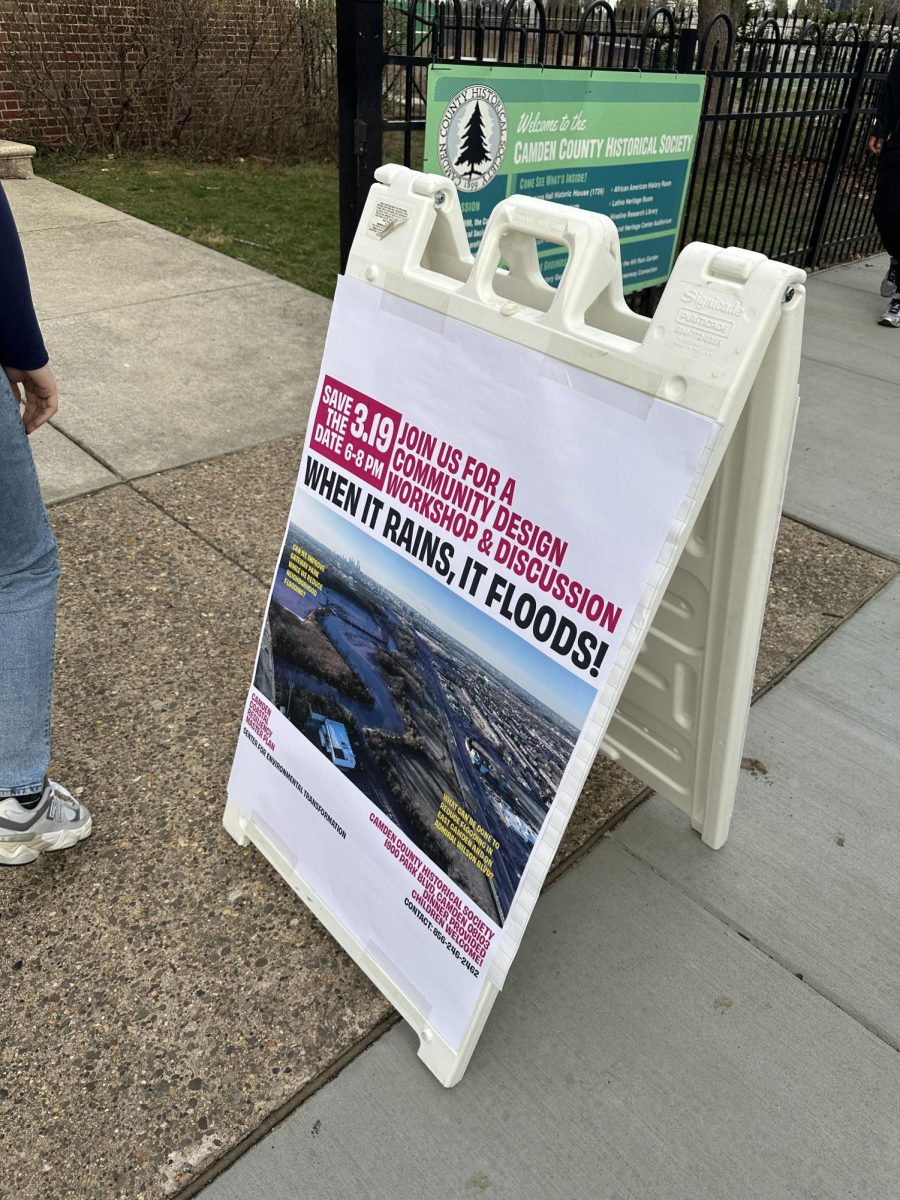

Fortunately for the residents of Camden, there are a variety of organizations in the city with intentions to improve it and highlight its inner beauty. Angel Perez, co-executive director of the Center for Environmental Transformation, an environmental organization located at 1729 Ferry Ave., said Camden has a lot of positive attributes that are often overlooked.

“Camden has a lot of beautiful things going for it,” Perez said. “It’s one of those things where you have to change the narrative.”

Camden was once a thriving city with one of the first railroads our country had to offer to its citizens, the Camden and Amboy Railroad. Camden was an industrious city that managed to house many small manufacturing companies as well as commercial offices.

Camden today is an exciting place to visit. Its waterfront features the 200,000 square foot Adventure Aquarium, erected in 1992 at Wiggins Waterfront Park, as well as the Waterfront Music Pavilion (formerly known as the BB&T Pavilion and Susquehanna Bank Center), and the Blockbuster-Sony Music Entertainment Center, with a large 25,000-person occupancy. The waterfront also includes the Hilton Garden Inn Camden Waterfront Philadelphia, which is 4.1 miles away from the City of Philadelphia right across the Delaware River.

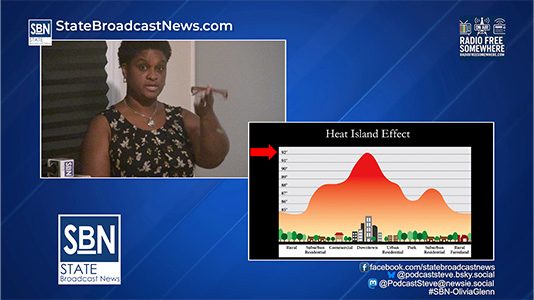

Yet, other areas of Camden continue to languish, struggling to house and educate its own residents. The city is seeing a high level of children with learning disabilities. In addition, the city has become a warehouse for toxic facilities, its citizens are not breathing in just one chemical at a time or one pollutant at a time, they are exposed to a barrage of pollutants. Thus, it is danger of being a sacrifice zone.

“CFET is still fighting a good fight, happening on a local, state, and national level to change things in a big way,” said Perez.

“Our goals lie on one main principle and that is building links with other communities,” he added. “We have been trying to establish coalitions with some of these organizations such as the Ironbound Core Corporation located at 317 Elm St, Newark, NJ.”

Newark

The Ironbound Community Corporation (ICC), which was founded in 1969, is an organization in the Ironbound section of Newark. According to its website, ICC is dedicated to engaging and empowering “individuals, families, and groups in realizing their aspirations and working to create a just, vibrant and sustainable community.” With a following of approximately 2,500 on Instagram, 2,000 followers on Twitter, and 140 subscribers to its YouTube channel, titled “Ironbound Community Corp ICC,” awareness of this organization is spreading rapidly.

The Ironbound composes most of Newark’s East Ward City Council district, covering four square miles. The area was the focus of “The Sacrifice Zone.” The Ironbound’s residential community, with Ferry Street as its spine, is interspersed with commerce, covering roughly a third of the neighborhood. The surrounding industrial area includes trucking, and chemical and waste businesses.

Houston is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

The name Ironbound, according to ironboundcc.org, is “derived from the many forges and foundries and railroads that once encircled it.” It is bound by Penn Station and the Amtrak line on the west; the Passaic River – the nation’s longest Superfund site – on the north, US Routes 1 and 9, the NJ Turnpike, and Port Newark on the east, and US Highway 78 and Newark Airport on the south.

The Ironbound features restaurants, bakeries, and markets that were evoked by culinary traditions from Irish and German immigrants to the United States from the 1800’s, who brought their European culture into these eateries. In addition, the Ironbound has cultural festivals and soccer clubs, causing it to become a desirable area to visit, invest in, and permanently reside in.

The Ironbound also is an economic engine within Newark, driving 40% of its economy and contributing to 33% of its tax base. Today local factories, warehouses and industrial properties continue to operate alongside one-, two- and three-family homes and public housing complexes.

Yet, while Ironbound’s industry has been a force in the local and regional economy, it has also caused significant environmental degradation. The inordinate amount of air pollution and land contamination impacts public health and quality of life, leading the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to classify Ironbound as an “Environmental Justice Community.”