By Faiza Zaman

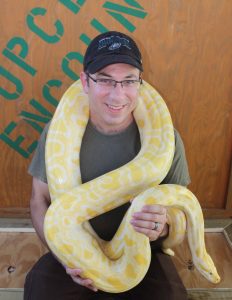

Dr. Dan Duran, Assistant Professor, School of Earth and Environment, and a researcher, educator, entomologist and forager, and is affiliated with Scotland Run Park in Clayton, N.J., met with us last spring to speak about environmental issues and eco-friendly projects in the South Jersey area.

Q: What environmental projects are occurring in Scotland Run Park Right?

A: We have a lot of educational as well as research-based projects going on right now. First off, we’re teaching kids about nature in our “Nature Tots” program. We think that having an appreciation for nature early on enables people to become better-informed citizens later in life. We have an “Adult Naturalist” program where we can dive more deeply into the natural world. On the research-side, we’re studying the biodiversity of Wilson Lake. I’m working with Rowan’s Biology Department to start looking at the phytoplankton communities in the lake, and the effects of herbicides on these communities and what that’s doing to fish and other organisms.

One thing that we really like to do is to give interpretive naturalist opportunities at our park, where people can see, up close, local biodiversity because so much of nature education reinforces the idea that nature is far from you, it’s in a place like Africa or Thailand, or somewhere you will probably never get to. Whereas there’s a lot of wonderful diversity right here in Gloucester County, right here in South Jersey, and now people can come into our Nature Center and see live animals and see displays of species that are from here. I think it’s important for people to have that local connection.

Q: Tell me about your environmental research.

A: I am interested in identifying the units of biodiversity – species, using different types of data. I employ different kinds of analyses including molecular data, morphological data, ecological data, all to determine the best ways to delineate species. Most of conservation is species-based and so, without a clear understanding of what constitutes a species, we cannot efficiently conserve biodiversity.

Q: What projects are you working on right now?

A: Right now, I am working on some projects that are more ecology based. I actually just started a collaboration with Cape May County Mosquito Control, and we’ll be looking at the effects of spraying aerial insecticides on insect biodiversity in general and on certain groups that we really care about, like pollinators. We’re going to be looking at the effects of pesticides commonly used to kill adult mosquitos. If we lose non-pest insects, like pollinators, it could affect our crops, native plant communities, so we’d like to know what these sprays are doing to non-target insects. Quite frankly this topic has not been researched thoroughly, some of the most common insecticides that we are now spraying to try control mosquitos have never rigorously been tested to see what kinds of collateral damage they are doing.

Q: As an expert in entomology, how do you use insects to help prevent environmental problems?

A: We can’t survive without insects. Insects are arguably the most important biodiversity on this planet. In fact, 90 percent of plants cannot reproduce without insects, they use insects as their pollinators. Unfortunately, we spend a lot of time thinking about the pest species of insects, which are a very small percentage, but we do not think as much about all the beneficial insects out there. There are more species of predator insects than there are insect pests. So, when you have a greater diversity of insects around, you have fewer pests. That surprises people.

Q: You teach an unconventional class, which is “Foraging for Edible Plants.” Can you tell me about that?

A: Yes, I teach a class at Rowan called, “Foraging for Edible Plants.” This is not a typical course. Students learn skills such as how to differentially diagnose species, being able to accurately identify similar-looking plants, and separate poisonous ones from edible ones. We talk about evolutionary ecology and how humans have evolved as foragers, and how we have switched to an agricultural lifestyle. We discuss some of the nutritional and physiological changes that have occurred as a result of this. It’s been an interesting experience, and students have definitely been interested in the material. I’m really glad I have an opportunity to teach something like this at Rowan.

Q: How is foraging beneficial for the environment?

A: This gets into the foraging – agriculture continuum. Foraging is going out into the woods and eating something from a shrub, etc., and that is one extreme. The other extreme is consuming mass-produced agricultural products that come from just a few species of exotic plants. And there is a lot of room in between and we can find sustainability in this area. For example, there is edible landscaping, a situation where you have your landscape plants that are used as ornamentals but you also go out and you harvest food from them. It may not be formal agriculture and it may not be exactly foraging, but it is something in between. Other, in between, ideas include growing food on green roofs and community gardens. Anything that can get us more off the “agricultural grid” is good because modern agriculture is one of the most unsustainable things that we do. The chemical inputs, the water inputs, the environmental destruction… It would be good if we can rely more on plants that we forage for on our own yards.

Q: How can South Jersey’s residents become more sustainable?

A: Very few residents know the importance of landscaping with plants that are native to South Jersey or at least North America. We have all these exotic ornamental shrubs in horticulture, some of which are very detrimental, ecologically. For example, a common plant that people can buy at Home Depot or Lowe’s is Japanese Barberry. It’s going to sound shocking, but it’s well documented that this plant actually increases our chances of getting Lyme Disease. A lot of these exotic shrubs cause major changes to the animal communities and that can affect disease transmission. These are creating scenarios in which one particular mouse can get to extremely high population densities, because they really like to live in the roots of this Japanese barberry and this mouse is the main vector for the infectious agent that causes Lyme disease. It matters what plants you put in your yard and what chemicals you spray in your yard. These are all things that are really important. Sustainability starts in our yards.