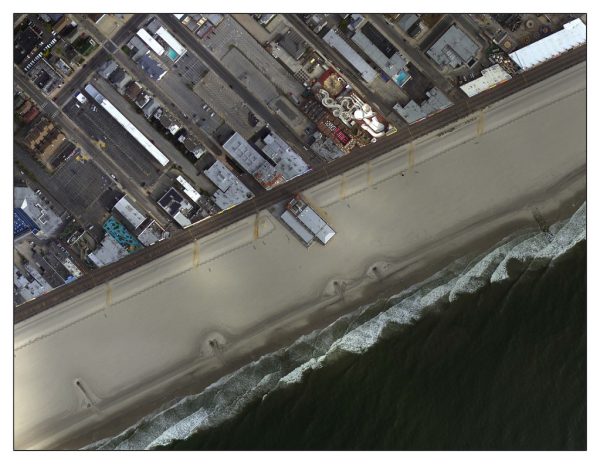

Beachgoers enjoy the sun and sand at Ocean City, N.J. (Photo by Dough4872, CC BY-SA 4.0

It’s a beautiful summer day in Ocean City, New Jersey. The sun is shining, seagulls are soaring overhead, and there’s a gentle breeze. But on the horizon, dark clouds start to build. Within a short moment, rain is pouring down, and the streets are suddenly under several inches of water. Unfortunately, with rising sea levels, this scenario is becoming increasingly likely.

The ever-present effects of climate change mean that flooding is becoming more common in coastal towns like Ocean City, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Even on sunny days, high tides can cause extreme overflows in these areas. These increasingly frequent events are manageable, according to city officials, but the scientists and experts who study the steady creep of sea level rise in New Jersey strike a much more cautious tone.

Climate Central, an independent non-profit made up of scientists and communicators who research climate change, found Ocean City—home to 9,150 people and 7,254 homes located 5 feet from sea level, according to Risk Finder—to be one of the most threatened New Jersey beach towns. The rise of sea levels negatively affects a variety of societal, environmental, and economic issues.

Ocean City’s Public Information Officer, Doug Bergen, outlined Ocean City’s 2025-2029 Capital Budget Plan, released this past February, as shown in the Ocean City Centennial, which describes the city’s flood infrastructure plans for the upcoming years.

“Among Flood Mitigation Projects in the capital plan, $500,000 is allocated in 2025 for the design of an elevation, drainage, and pumping station project for the ‘Ocean City Homes’ neighborhood in the area on the bay side between 52nd Street and 55th Street,” Bergen said in an email interview. “The $4 million in 2026 is for construction of a similar project in a low-elevation neighborhood between 18th Street and 26th Street (this project is currently under design). The $5 million in 2027 is for construction of the Ocean City Homes project.”

In a Feb. 26 weekly update to Ocean City residents, the city’s Mayor Jay A. Gillian seemed optimistic about the city’s ability to face this challenge, with less spending allocated to flood mitigation projects compared to previous years.

“The plan projected that fewer projects would be necessary over time, and we would begin to be able to decrease annual funding,” Gillian said. “Our new capital plan reflects that decrease. We will now start to see our annual debt-service costs level off in the coming years.”

However, with flooding events occurring more frequently, it is unclear if the capital plans of coastal towns like Ocean City are enough.

“It’s absolutely not enough,” said New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s (NJDEP) Chief Resilience Officer Nick Angarone.

Angarone said he believes the city needs to better plan for the future. For example, Ocean City’s new building regulations required by the state are taking into consideration an anticipated five-foot increase in sea level by the end of the century. Even that may not be enough, however, to address the long-term effects of climate change.

“You need to understand what’s coming to know how to best respond to it.” Angarone said. “Again, we’re planning for five feet, and we’re getting a lot of pushback: ‘That number is too high, it’s going to be too expensive.’

“We’re basing our policy decisions on the best available science, so understanding that that’s coming, whether you like it or not,” he said. “I think longer term, you have to start considering whether you’re going to be able to stick it out there if you have up to five feet of water in your community every day. Is that sustainable?”

Tom Herrington, the associate director of the Urban Coast Institute at Monmouth University and co-coordinator of the New Jersey Coastal Resilience Collaborative, said Ocean City’s streets and original structures were not built with rising sea levels in mind and have undergone significant changes in recent years to account for the rise in sea levels.

“The infrastructure in the city was built between the 1920s and the 1960s,” said Herrington. “Everything is very low… All the infrastructure stayed in the same place. But the sea level has been rising. The last 100 years, it’s been about a foot and a half, but we certainly expect that to increase with increased warming of the ocean and the melting of the overland ice caps.”

Some solutions include pump stations that capture the rain water and then pump it out. Unfortunately, this solution is incredibly expensive, and it only provides temporary relief. These pump stations are also designed to deal with damage after the fact, not acting as a proactive solution.

“The problem is that sea level is not going to stop rising, and eventually those water levels will be coming across the lower elevations along the edge of the bays,” said Herrington. “So there’s some natural areas still along the back bays where water will come across the marsh, up into the streets, or, you know, very low bulkheads will be inundated, so the problem is going to persist and get worse.”

The New Jersey Coastal Resilience Collaborative was developed to stabilize the shoreline by prioritizing resiliency with nature-based solutions and conserving tidal marshes, oysters, and shellfish habitats. The NJDEP formed the collaborative following Hurricane Sandy, and it has since grown immensely.

“It’s a pretty effective partnership to get projects, bring funding into the state, and implement some of these ideas on the ground,” said Herrington.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers also works with the city to combat the effects of sea level rise. Steve Rochette, the chief of public affairs at the Army Corps’s Philadelphia District Office, has seen a shift in the city’s line of defense in terms of climate change following Hurricane Sandy.

“Since Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the Corps has observed a significant increase in awareness of the risks that our coastal areas are under, in terms of infrastructure, [and] that knowledge and awareness has increased from the public,” said Rochette.

According to Rochette, unless the proper measures are taken, Ocean City could see average annual damages of about $2.6 billion. The Army Corps is focused on taking the appropriate steps to implement structural measures like storm surge barriers and seawall projects.

“We think of ourselves as an important partner to [the NJDEP] in terms of managing big and small studies,” Rochette said. “There’s always going to be risk, but we’re essentially looking at ways to help manage it.”

According to Angarone, partnerships like the one the NJDEP has with the Army Corps are invaluable to the effort to combat climate change.

“No community in New Jersey is going to be able to address this on their own… whether the state and the Feds should prioritize helping communities who are less fortunate or less wealthy than Ocean City, I think is a very important policy question,” said Angarone. “We are going to have to start making difficult decisions about where our funding goes, and if that means that Ocean City is able to support itself without that additional external support, then good for them. But I think ultimately we’re looking at kind of a broader, at least statewide or region-wide response to the vulnerabilities.”

Efforts to help with the effects of sea level rise don’t solve the problem overnight. Communities have a lot of work to do.

“As always, these impacts affect first and worst, those who are least able to respond; our lower income and our socially vulnerable populations, the communities we’ve been systemically underfunding them for decades…long term, we have some really, really difficult decisions we’re gonna have to make, and it’s gonna be really, really expensive…so I think everyone needs to do a vulnerability and a risk assessment,” said Angarone.